Review of Author Cixin Liu's "Supernova Era"

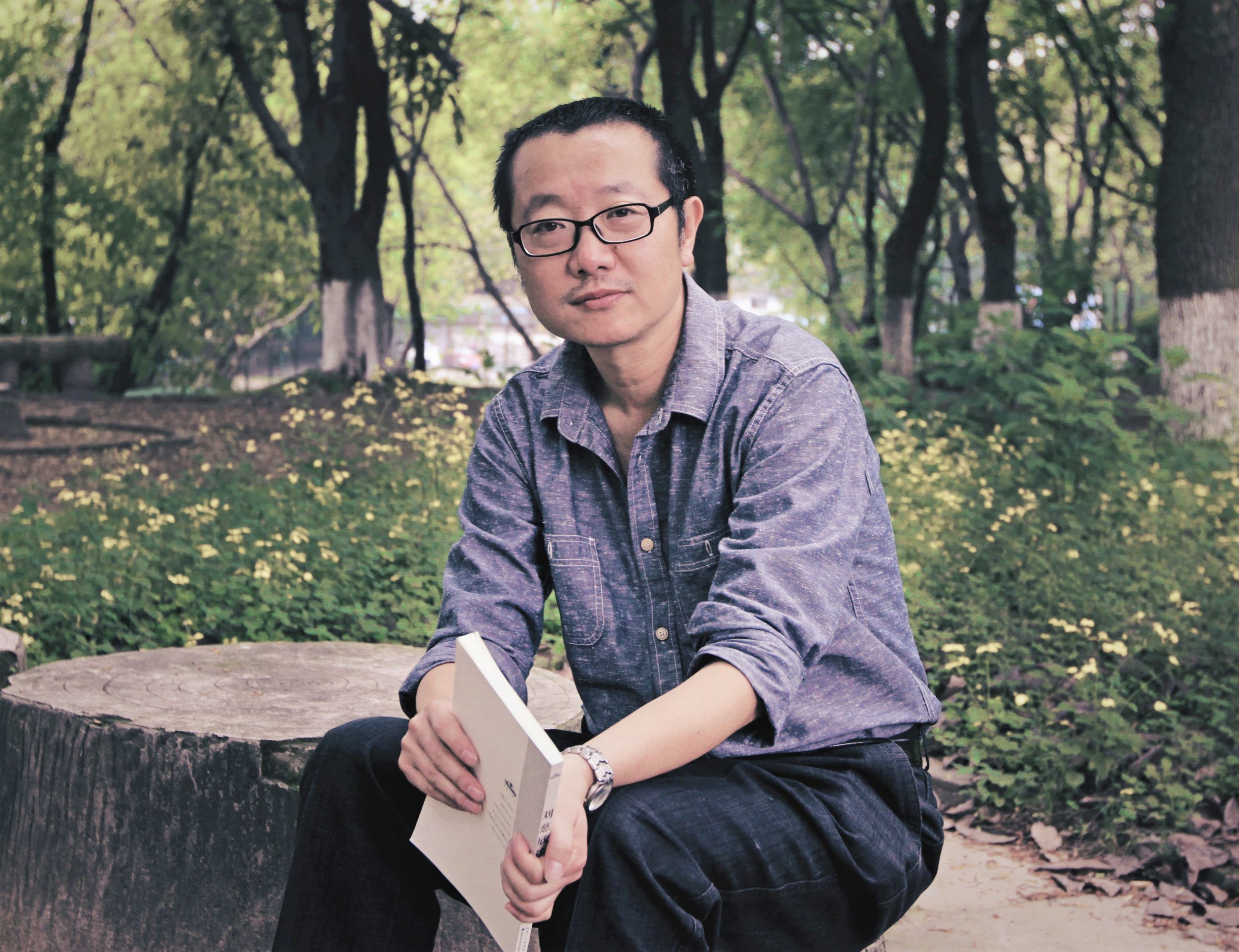

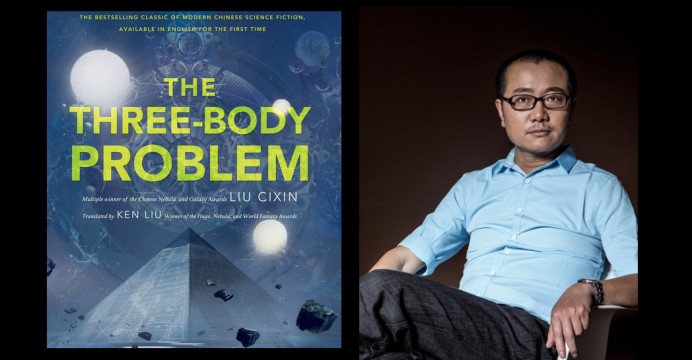

Author Cixin Liu

A different side of China's Revered Sci-Fi Author

Cixin Liu’s latest work, Supernova Era (launching this October & published by Tor Books), begins with a terrifying event—eight light-years from Earth, a dying star explodes into a supernova. Undetected by the world’s astrophysicists, the Earth takes a direct hit from massive waves of radiation, with disastrous effects rippling across the globe.

Though many of the fauna and flora of the Earth wither, miraculously, the chromosomes of children thirteen years and younger are unaffected, and the dying parents discover their children will survive the maelstrom. But what happens when children inherit the Earth?

For readers not familiar with Liu Cixin (publishing under the name Cixin Liu), he burst onto the western scene with his novel, The Three-Body Problem, by winning the Hugo Award in 2015, the first Asian writer to snag the award. The novel was also a 2015 Campbell Award finalist and garnered a nomination for the 2015 Nebula Award. In China, his works have received multiple awards and he has risen to be one of the leading voices in Chinese science fiction. He cites Author C. Clarke's intricate world-building as a major influence in his works.

Liu was born in 1963 (Yangquan, China) during the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution—a major impact on his life. Liu was educated at the North China University of Water Conservancy and Electric Power, and then worked as a computer engineer. [primary source: Wikipedia]

Liu’s artistic side blends seamlessly with his engineering chops. In his hands, physics becomes a palette of color and texture—he illustrates the supernova’s impact on the world in poetic prose: “... its light scattered in the atmosphere, turning it into an enormous, blinding, poison spider hanging in the western sky.”

However, unlike his Remembrance of the Earth’s Past Trilogy, Liu’s Supernova Era reveals another side of this creative science fiction author as he spins a tale, written like a history book, of how a random stellar occurrence kills off the adults of the planet, leaving the children to run the world.

Excerpts from the book:

In those days, Earth was a planet in space.

In those days, Beijing was a city on Earth.

On this night, history as known to humanity came to an end.

Influenced by writers such as George Orwell and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (written as a reaction to World War II), Supernova Era takes on a nightmarish societal treatise. Liu wrote the novel in 1989 while in Beijing just before the Tiananmen Square massacre. He describes that night:

In June of that year [1989] I was in Beijing, a city in the midst of political turmoil, and on the night of June 4, I listened in my hotel to the chaotic noise outside, and the muffled sounds of gunfire. That night I dreamed of a limitless expanse of snow, whipped up by the wind into a ground blizzard, and an object—perhaps the sun or a star—glowing with a blinding blue light that painted the sky an eerie color between purple and green. And beneath that dim glow, a formation of children advanced across the snowy ground, white scarves wrapped around their heads, rifles fitted with gleaming bayonets, singing some unrecognizable song as they moved forward in unison. . . . When I recall the horror of that grim scene it still gives me palpitations. I awoke in a cold sweat and couldn’t get back to sleep, and that’s when the germ of the idea for Supernova Era first took shape.

In Supernova Era, an innocent child’s voice recites the terror of a chaotic world held hostage by puerile leaders. Though Cixin Liu writes from a Chinese perspective, his stories highlight the universality of the human experience—the darkness and light—the love and fear—that exist within us all.

Supernova Era was translated into English by Joel Martinsen.

This review was initially published on FUTURISM: Review of Author Cixin Liu's 'Supernova Era'

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

SUBSCRIBE TO K.E. LANNING TO RECEIVE BLOG ARTICLES AND AUTHOR UPDATES

What if the ice caps melted . . . in one human lifespan?

Deep Break

“Deep Break” is an antiquated method of plowing when the soil is overturned and exposed in the early spring to ready the soil for new growth. As I construct my work-in-progress, Where the Sky Meets the Earth, I, too, dig for roots deep in history to create my novel, gathering research to develop both plot and character.

Where the Sky Meets the Earth is a work of literary fiction delving into the consequences of the recent economic fallout entangled with a perceived second coming of a messiah (think a twist on Stranger in a Strange Land set during the Great Recession). A nuclear family has exploded—unemployment, opioid addiction, and divorce. The son, a fourteen-year-old mixed-race boy, disappears into the mountains of Wyoming, seeking a true way of living.

Preliminary cover art

In order to weave a complex story such as this, it takes hours of sifting through threads of history; research on the causes of the Great Recession and the impact on the lives of ordinary people. In order to build the Arapaho shaman character who becomes the lightning rod at the center of the story, I read indigenous history books such as The Wisdom of the Native Americans and In the Hands of the Great Spirit.

But a book that truly resonated with me was an incredible work by Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, published initially in Hebrew (2011), then in English in 2014. This is a stunning book on the anthropology of homo sapiens, and various competitor humanoids, up to the present time. This is not a dry rendition, it is filled with Harari’s philosophical spin on the effects of capitalism, government, and religion.

I was particularly interested in researching the hunter/gatherer period before homo sapiens became trapped into the agricultural revolution, which begs the speculative question—how would society look if that leap hadn’t occurred? And as my novel will attempt to reveal—what if a new messiah led us back to the hunter/gatherer life—turning away from modern society?

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

SUBSCRIBE TO K.E. LANNING TO RECEIVE BLOG ARTICLES AND AUTHOR UPDATES

What if the ice caps melted . . . in one human lifespan?

Cli-fi Meets Biopunk?

Paolo Bacigalupi (Photo by JT Thomas Photography)

Author Paolo Bacigalupi’s debut novel, The Windup Girl [published in 2009 by Night Shades Books], celebrates its 10th anniversary this fall. Critically acclaimed, it was named one of the top 10 fiction books in 2009 by TIME Magazine and won the 2010 Nebula Award, the Campbell Memorial Award, and the 2010 Hugo Award in a tie with China Miéville’s The City & the City. The novel has become one of the defining works of biopunk, a sub-genre of science fiction which explores dystopic worlds of genetic manipulation by power brokers.

The Windup Girl is set in 23rd century Thailand, barricaded with a massive levee system shielding the island from rising sea levels due to global warming. The kingdom, thus isolated from the human-induced plagues of the world, contains the remaining genetically viable seeds on Earth. Within this climate fiction (cli-fi) and biopunk fusion, Bacigalupi weaves an intricate tale of political intrigue between mega-corporations and politicians fighting for control over the last untouched seedbank, complicated by Emiko, an illegal Japanese “windup,” a genetically modified human created as a pleasure doll, but who revolts from her programmed impulses in order to free herself from sexual slavery.

However, this mashup of biopunk and cli-fi subgenres started with Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy of speculative fiction: Oryx and Crake [2003; shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and the Orange Prize for Fiction], The Year of the Flood [2009; 10-year anniversary], and MaddAddam [2013]. Though global warming has affected Atwood’s near-future Earth, the multifaceted trilogy revolves around genetic engineering gone bad—really bad.

Margaret Atwood (Photo by Liam Sharp)

In this apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic saga, Atwood tells an exquisite story of love and madness, but whether the insanity lies within the brilliant geneticist or within the malaise of a broken world is left for the reader to decide. Reminiscent of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses, Atwood masterfully pieces together flashbacks and parallel scenes from different viewpoints, until the overarching story clicks deliberately into place, like a brilliant Rubik's Cube. For you CliffsNotes folks, let me break it down: A complex tale of love in a f#%k-upped world. Get it. Read it. Rumor is the trilogy might be coming to the screen…

The terrifying reality is that our world of genetic engineering is no longer fiction. Like Aldous Huxley’s “fantasy” novel, Brave New World, ready or not, we are on the cusp of a biotechnology revolution. CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) has its roots in the mid-1980s, but major advances in genome editing sprang up in this century. On November 28, 2018, a Chinese scientist, Jiankui He, announced that he had created the world’s first gene-edited babies. And so Pandora’s Box has opened.

Fears over climate change and genetic engineering are threads within the stomach-knotting anxieties of the new millennium. The beginning of the 2000s saw horrific terror attacks around the globe, unending wars in the Middle East, and instability in Europe. As the century continued, a financial meltdown sent economic woes rippling across the world, with unemployment exacerbated by the rise of technology. (Is the angry backlash of populism truly a surprise?)

Behind the curtains of our partisan battles and economic instability, puppet masters jerk the strings of political “hostages” for their own benefit. And we capricious humans play god—global warming melts the Earth’s ice caps and genetic engineering leapfrogs over human morality. But as the tenets of society erode amidst the angst of this new century, a thirst for “why” and “what if” drive writers to attempt to make sense of it all, spinning parables of warning to an unsuspecting, or simply complacent, humanity.

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds {2019]

What if the ice caps melted . . . in one human lifespan?

This article was also published in FUTURISM magazine: Cli-Fi Meets Biopunk

I’m OK, You’re Not so Great

For a brief moment, I breathe a sigh of relief at the completion of a trilogy (The Melt Trilogy) which has consumed me for years. But there is no rest for the weary—I leap into my next Work-in-Progress, Where the Sky Meets the Earth, outlining the plot and characters, letting my mind wander as I step into the cold, dark waters of a new novel. The other day, musing over my nascent characters, a book that I had read decades ago popped into my consciousness: I’m Okay, You’re Okay, written by Thomas A. Harris, M.D [1967]. Harris linked studies performed by brain surgeon Wilder Penfield, who stimulated the brains of conscious patients during surgery, eliciting vivid memories from his patients, with experiments from Eric Berne, who developed the ego-state models we acquire as humans interacting in the world: Parent-Adult-Child [Transactional Analysis].

In his book, Harris simplified these internal/external feelings and subsequent interpersonal transactions into four categories: 1) I’m Not OK, You’re OK, 2) I’m Not OK, You’re Not OK, 3) I’m OK, You’re Not OK, and finally (Whew) 4) I’m OK, You’re OK. According to the studies, people who were abused as children may conclude that 1 or 2 is their go-to place, whereas a con-artist may be happiest in the I’m OK, You’re Not OK existence. But Harris goes on to describe hybrids of these positions; contaminated Adult states via forms of prejudice by a Parent, or delusions from childhood memories influencing the Child within us. Hopefully, most “normal” folks are in the I’m OK, You’re OK in their attitudes, but who wants normal in their novels?

As a writer interested in creating flawed humans, not caricatures, sculpting realistic characters from clay can benefit from utilizing these various “programmed” human responses. Did the character have a happy or horrible childhood? How might a damaged soul react when confronted?

An editor once told me that one of my male characters should immediately respond to a rather personal question posed to him. I disagreed—many people simply change the subject, and either never respond or respond only when they feel secure. For those characters, body language is their primary communication.

Can these rather simplistic interpersonal responses help guide an author as to whether the dialogue or action is appropriate for the character given their specific background? Perhaps, for we humans are creations of our past, regardless of how we attempt to mask the scars beneath the surface.

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds {2019]

What if the ice caps melted . . .

in one human lifespan?

Review of Claire Vaye Watkins' novel, Gold Fame Citrus

As California burns . . .

Claire Vaye Watkins - Photo credit: Lily Glass Photography

No matter how you slice and dice author Claire Vaye Watkins, she is an important new voice in literature. Watkins was born in 1984 in Bishop, California to her dynamic mother, Martha Watkins, and her father, Paul Watkins, a former member of the Charles Manson Family. She grew up in the Mohave Desert, in Tecopa, California and Pahrump, Nevada—the desolate landscape a clear influence on her writing. She graduated from the University of Nevada Reno and then earned her MFA from Ohio State University where she was a Presidential Fellow.

Watkins sprang onto the scene with Battleborn [2012], and her debut short story collection won a multitude of literary prizes: the Story Prize, the Dylan Thomas Prize, the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Fiction Award, the Rosenthal Family Foundation Award, and a Silver Pen Award from the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame. Her writing chops led to several honors: a Guggenheim Fellow, one of the National Book Foundation’s “5 under 35” and Granta’s “Best Young American Novelists.” Her stories and essays have appeared in respected publications, such as Granta, Tin House, Freeman’s, The Paris Review, Story Quarterly, New American Stories, Best of the West, The New Republic, The New York Times, and Pushcart Prize XLIII.

I read her speculative fiction/cli-fi novel, Gold Fame Citrus [2015] as California fires obliterated entire communities in the blink of an eye. The novel was named the Best Book of the Year by The Washington Post, NPR, Vanity Fair, LA Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Huffington Post, The Atlantic, Refinery 29, Men's Journal, Ploughshares, Lit Hub, Book Riot, Los Angeles Magazine, Powells, BookPage, and Kirkus Reviews.

The story is set in a near future of extreme drought on the West Coast when most have fled the Golden State as giant dunes devour the land. What remains in the desert are the dregs of society, skittering like bands of rats over the leftovers of the rich and famous. The two main characters, Luz, a former poster child, and Ray, an army deserter, flow through this landscape like grains of sand tossed in the wind, unable to direct their lives. At a gathering of vagabonds, a child appears, lost and yet not lost. Luz decides to take the child and raise her, but the decision shoves them onto a path they had not planned. They flee east into the sea of dunes, imperiling their lives—and their souls.

Gold Fame Citrus is not a happy-go-lucky novel—think Lord of the Flies meets The Treasure of the Sierra Madre—but Watkin adds touches of humor into the crevices of her story, particularly wrapped around the character of Sal, exposed to the outside world through a pin hole of bizarre television shows, such as “Embalming with the Stars” and “Midgets of Middle Management,” and who befriends Ray when he finds himself trapped in Limbo Mine.

Reminiscent of Huxley and LeGuin, Watkins expertly weaves strands of metaphor and angst into this dystopian parable reflecting the ugliness and tenuous nature of humanity on the edge of survival. The insane, the desperate, and the unlucky gather in the middle of the desert into a tribe, devolving into hunter-gatherers, and ruled by an enigmatic master. The fantastical world Watkins creates on an ocean of sand, scattered with peculiar and broken characters, is more akin to a disturbing Alice in Wonderland than “what if” climate fiction. In fact, Gold Fame Citrus is a searing revelation of our human condition and the deep wounds within that never heal, crippling us along our journey in life.

Both a writer and teacher, Watkins is currently a professor of creative writing in the Helen Zell Writers’ program at the University of Michigan, following assistant professorships in creative writing at Princeton and Bucknell. She is the director and co-founder, with spouse, Derek Palacio, of the Mojave School, a festival of art and literature, supporting young writers in Pahrump, Nevada.

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds {2019]

This review was originally published on FUTURISM on November 13, 2018.

Review of Mary Doria Russell’s "The Sparrow Series" on its 20th anniversary

They meant no harm.

Mary Doria Russell Photo credit: Don Russell

Author Mary Doria Russell was born in Elmhurst, Illinois, into a military family, her father a drill instructor in the Marines and her mother a nurse in the Navy. Raised a Catholic, she left the church as a teenager, but the struggle to parse faith and the role of religion is etched into her works. Russell earned an undergraduate degree in Cultural Anthropology from the University of Illinois [Urbana-Champaign], a M.A. in Social Anthropology at Northeastern University in Boston, and a Ph.D. in Biology Anthropology at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor.

As an author, Russell refuses to be bound to writing within a specific genre—her WWII novel, A Thread of Grace, is a masterpiece of historical fiction based on well-researched accounts and interviews, and a story rarely told of the Italians’ role in saving Jews fleeing from the Nazis. With her superlative research chops, no matter if her novel is set in the future or in the past, she excavates the bones of a story, searching for the life below the surface, and creating characters from the dust to tell the tale.

Mary Doria Russell’s debut novel, The Sparrow, exploded on the scene in 1996, followed by the sequel Children of God in 1998, and this year marks the twentieth anniversary of the completion of The Sparrow series. Critically acclaimed, The Sparrow won multiple honors: The Arthur C. Clarke Award, the James Tiptree, Jr., the Kurd Laßwitz and the British Science Fiction Association Awards, to name a few.

Speculative fiction at its best, The Sparrow weaves Russell’s beautifully developed characters into a story of multifaceted social commentary as fresh and searing as when it was first published. Russell infuses several of her novels with religious references, and the title of The Sparrow is no exception. In the Gospel of Matthew 10:29-31, “. . . not even a sparrow falls to the earth without God’s knowledge thereof.”

The Sparrow is set in the near future [year 2019!] when scientists at the Arecibo Observatory detect radio broadcasts of music from the vicinity of Alpha Centauri, originating from an earth-like planet named Rakhat. The Society of Jesus, the Jesuits, known for their missionary, linguistic, and scientific endeavors, underwrite a voyage to Rakhat, via a modified asteroid, to establish first contact with the planet. The main character, Father Emilio Sandoz, a Jesuit and a superb linguist, believes that God has assembled this group of people, with unique skills and talents, for this mission.

But all is not as it seems when they reach the planet of Rakhat. The crew descends to the surface and acclimate themselves to the new world, studying the fauna and flora of this Eden, and eventually make contact with a tribe of sentient herbivores, the Runa. Emilio Sandoz learns enough of the Runa language to communicate with the gentle creatures and realizes that they are not the ones broadcasting the music. A trader, Supaari VaGayjur, of the Jana’ata tribe, the dominant and carnivorous species on the planet, visits the Runa village, and the expedition discovers that these are the beings broadcasting the songs.

The story deftly flashes back and forth in time from the events during the trip to “present” day after the return to Earth of the only apparent survivor of the voyage, Emilio Sandoz, who is suffering from both physical and mental wounds—and facing a moral crisis in his faith in God.

The Children of God, the sequel to The Sparrow, picks up the story of a shattered Emilio Sandoz, who has rejected God and the priesthood. After the slow healing of his body and mind, Sandoz is now training a new crew for a return mission to Rakhat to find the lost crew members and re-establish contact with the beings on the planet. The story reveals that in the decades since the first mission, a rift has occurred in the social fabric on Rakhat—sparked from human influence.

In The Sparrow Series, Russell delves into the consequences of human interaction with alien life. When humans do make first contact with a sentient being, will they be prey or predator? Will our religious beliefs survive the brave new world of interstellar travel? Just as Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle predicts, observations and contact can affect those being observed, and potentially affect the observers as well, leading to moral dilemmas of epic proportions. A quote from the book says it all: They meant no harm…

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds {2019]

This review was originally published on FUTURISM on October 23, 2018: https://futurism.media/review-of-mary-doria-russells-the-sparrow-series-the-20th-anniversary

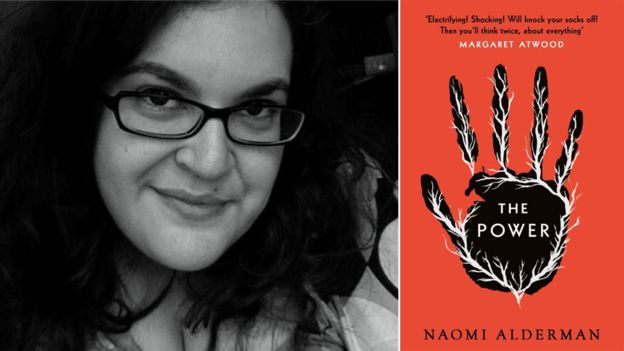

Review of Naomi Alderman's 'The Power'

Naomi Alderman

Never one to be pigeon-holed, Naomi Alderman is a British novelist, game writer, and radio host. As a writer, she is fearless. Her debut novel, Disobedience, published in 2006, immerses the reader into an Orthodox Jewish community through the eyes of a rabbi’s lesbian daughter. Controversial, the novel was critically acclaimed and the San Francisco Chronicle described the story as “acerbic and self-aware.” The Sunday Times named her their Young Writer of the Year in 2007 and Waterstones included Alderman in their 25 Writers of the Future. Her second novel, The Lessons, was published in 2010 and her third novel, The Liars’ Gospel, followed in 2012. Alderman was appointed professor of Creative Writing at Bath Spa University in 2012 and was included in the British Granta list of 20 best young writers in 2013. In 2012, during the writing of The Power, Margaret Atwood selected Alderman as her protégé as a part of the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative, an international philanthropic program, pairing masters with emerging talents.

A stunning work of speculative science fiction, The Power is Alderman’s fourth novel, dedicated to her mentor, the venerable Margaret Atwood. In its essence, The Power is a treatise on the human desire for dominance. From the Greek tragedies through Shakespeare’s plays and now our ‘civilized’ society, the mad pursuit of power and revenge stains our past and colors our future.

Since our early evolution, women have, for the most part, been physically weaker than men. Our small tribal groups created a deep, instinctual need for close societal bonds, but also makes us vulnerable to abuse through this cultural hierarchy. Olivia Butler’s outstanding novel, Kindred, explores how humans, male and female, are conditioned to bondage, and ‘enslaved’ by the insidious mental, and sometimes physical, chains applied by their masters.

In Naomi Alderman’s novel, pollution has caused a mutation, primarily in women, which enables them to direct potent electrical charges through their fingers. The power structure of our society was built on the dominance of men over women. What happens in Alderman’s world when women are suddenly ascendant to men and our gender-based power roles switch?

This complex story is told from the viewpoint of four main protagonists, through the pen of a man conducting an archaeological dig, so to speak, as he researches this ancient and turbulent era. Alderman rips away the accepted facades of women when the taste of power reaches their lips. In a quote from the book, she writes, “Power doesn’t care who uses it.”

The plot is meticulously developed and the diverse characters fleshed out, but one aspect I would have been interested for Alderman to explore: how might this power shift have impacted an established love relationship between a woman and a man? Would the institute of marriage survive this sudden role reversal?

The Power is a fascinating, but terrifying look into a fun house mirror—what is up is down and what is down is up. Though published in 2016, it resonates in our ‘summer of discontent’ as it reveals the ugliness within the human beast, that place where the seed of fear germinates into societal madness.

In June of 2017, The Power won the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, and was named by The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, Entertainment Weekly and NPR as one of the 10 Best Books of 2017. The Power was one of President Barack Obama’s favorite books of 2017. Since its launch, the book has ridden the wave of the Me Too movement, pulling back the curtains on the ubiquitous, yet hidden abuses of power within our society.

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds [2019].

This review was originally published on FUTURISM on July 6, 2018: https://futurism.media/review-of-naomi-alderman-s-the-power

Review of Adam Roberts’ The History of Science Fiction

Author Adam Roberts

I’m a long-time fan of science fiction. I love the genre in its ability to expand the reader’s mind into the ‘what-if.’ I ran across a review Adam Roberts had published on Margaret Atwood, while I was writing an article on speculative fiction. I ultimately sent the piece to Roberts, and in so doing, discovered his book The History of Science Fiction.

Sometimes history can appear to be dry after the astringency of the moment has passed, but I found Roberts’ book fascinating in his meticulous excavation of ancient literature to discover the bones of science fiction. His thorough research progresses from ancient times to the opening of the twenty-first century to build a comprehensive history of science fiction, including sci-fi magazines, artwork, cartoons, film and television.

Roberts begins with a comparison of Greek mythology to science fiction by underlining how the human mind creates fantastical worlds in which to place heros and heroines into danger, both physically and morally. Particularly, the Greek tragedies were penned to magnify society’s ills and the weaknesses of the human soul. And because of our lingering humanity, these Greek tragedies are still compelling.

Likewise, many of the enduring modern science fiction stories delve into the psyche of society. Brave New World (Aldous Huxley), 1984 (George Orwell), Stranger in a Strange Land (Robert Heinlein), The Lathe of Heaven (Ursula K. Le Guin), and The Handmaid’s Tale (Margaret Atwood) dissect the extremities of the human condition, laying bare the diseased parts for all to examine.

As the book proceeds, Roberts speculates that without the Reformation, science fiction might not exist. I hold some skepticism of his entire premise, but there are points in favor of his theory. As Roberts expounds on the absolute power grip that the Catholic Church had on every aspect of society, including the sciences, I realized that he was on to something. For without liberty to freely research and publish the results, which might infringe on the centrist power of the Catholic Church, then to speculate in a science fiction sense is also forbidden. The blossoming of rational thought drove scientific discovery and the ‘what-if’ nature of science fiction, but the bonds of the Catholic Church had to be broken before free-thinkers could live without fear of excommunication or even death.

Science fiction came into its own during the Enlightenment—the time of Newton, the poetry of physics and the satires of Jonathon Swift and Voltaire. Roberts shows us how Swifts’ Gulliver’s Travels and Voltaire’s Micromégas are classic science fiction in their world-building via the ‘voyage extraordinaire’ and speculation of the human condition. Political turmoil created excellent fodder for writers, and in France, the French revolution sparked a surge in science fiction novels.

Throughout my life, I’ve read voraciously, including classic science fiction, and I loved the writings of authors such as Ursula K. Le Guin and Margaret Atwood. But I was happy to learn of, or in some cases, be reminded of, the numerous female sci-fi authors leading up to contemporary science fiction, such as Margaret Cavendish (17th century), Marie-Anne de Roumier-Robert (18th century), Mary Shelley and Jane C. Loudon (19th century). Roberts notes that the best screenplay written for the Star Wars films, The Empire Strikes Back, was written by Leigh Brackett. The biases of the times don’t always stymie genuine voices, but the history of these authors is many times forgotten.

The industrial revolution created a clash of technology versus humanity—nothing like angst and fear to drive a good sci-fi story. Roberts details the lives and influences of great writers such as H.G. Wells and Jules Verne. And I was amazed to learn how many well-known authors, such as Edgar Allan Poe, had dipped their pens into the science fiction well from time to time (pun intended).

The first half of the twentieth century was chaotic: two world wars, the advent of the atomic age, and the dawn of space travel. The excitement and anxiety of the twentieth century triggered a new wave of sci-fi and, with the advent of modern media, expanded into magazines, comics, film and television.

The disillusionment of the second half of the twentieth century brought a social consciousness and mysticism to the genre. The deft hands of talented sci-fi authors revealed a dark underbelly of our humanity, like Robert Heinlein’s, Stranger in a Strange Land and Margaret Atwood’s, The Handmaid’s Tale. In our current century, sci-fi has developed new sub-genres, such as cyberpunk and a fresh wave of environmental novels.

I particularly enjoyed the subtle humor sprinkled through-out the book: “The unfortunately named Richard Head . . .” Roberts also makes clear his opinions of the novels and authors, which I found enlightening and quite impressive that he himself had read the incredible collection of works that are referenced in this book.

As a sci-fi author myself, I know the derision some critics have for the genre, so it was with interest to read a quote Roberts included from essayist and literary critic, Sven Birkerts:

“Science fiction will never be Literary with a capital L . . .”

But author Hugh Howey’s [WOOL, 2011] answer to a similar question I posed in an interview with him in 2017, as to disdain of SF, perfectly illustrates the issue:

“I noticed this in my years of working in bookstores. Anything from the genres that was considered great was moved into the literature section. Frankenstein, A Handmaid’s Tale, 1984, Brave New World. Others were called “classics,” like [novels written by] Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. Retailers and publishers pluck all the best genre works and decide that they can’t be genre, because genre sucks and these things are good.”

I believe it is the booksellers who place a novel on a science fiction “shelf” and the one variable in this selection appears to be any story in which a time element is twisted whether into the past or the future. With the alteration of that one element as a sole variable, it seems silly, and frankly arrogant, to “trash” science fiction as not literary. In writing, it’s about the quality of the story and characters, just as these criteria are used to judge any literary work, whether it is “genre” or not.

Because of its ability to magnify the excitement of discovery or the ills of our society, science fiction is an important thread in our cultural fabric. A quote from the Roberts’ book I believe wraps up the essence of science fiction:

“SF is exhilarated by and superstitiously fearful of technological advance, or alien life, or the scale of the cosmos.”

Roberts parses science fiction into its multitudes of sub-genres with knowledge, respect and a touch of humor. Beautifully researched, this is a book for readers who enjoy history as well as science fiction—not a light read, but like a good dinner of prime rib and a glass of Malbec—a satisfying one.

K.E. Lanning, author of speculative science fiction: A Spider Sat Beside Her and The Sting of the Bee

This article has also been published on FUTURISM, March 2, 2018

The Margaret Atwood 2017 interview. This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

ASSEMBLY REQUIRED

I attended a writers’ conference the other day. As usual, it was filled with talks on marketing, publishing, and how-to improve your writing skills. And, as usual, it was during lunch that the most interesting conversations occurred. The small group I sat down to eat with was, as one writer characterized, “the onesies table.” She quickly explained that this table wound up being the table of authors who had come to the conference alone. Which isn’t surprising knowing that most writing is a solitary task. But is it?

The draft of a novel does tend to be a solitary act. But once that phase is completed, a team must built to bring the story to the publishing level. Traditional publishers have teams in situ to bring the steed into the grooming rack and curry away the mud and extraneous hair until a shining coat emerges. A slough of editors; developmental, copy-editors, and proofreaders, perfect the interior, while cover designers work their magic to create a cover to draw in the fickle reader. Then marketers, agents and publicists fluff up the author like a cardboard superstar on the internet. Photo shoots, public appearances, blogs, interviews, etc., etc., etc.

Courtesy of Hannsman Bookgroup

And the indie author must compete with all of that. Let me emphasize one word in the last sentence: MUST. If you, the next great author, want to be taken seriously, you must understand that writing the novel is a small part of the publishing puzzle. Believe me, I’ve had to run the indie gauntlet, and the scars are still there.

So you must think like a publisher and gather a team. Like a polygamous marriage, assembling your team is fraught with mind fields (pun intended). A published novel is only as good as your team and the weak link will sink you, so you must search out the best editors and cover designers you can find. And I mean search, ask, inquire of all of your author friends (did I forget to mention that you need author friends?). I have a development editor and a different copy editor. I emphasize, especially to the first editor to touch my baby, that I have a thick skin and I WANT them to literarily beat me about the head and shoulders. I haven’t hired them to be my friend, I’ve hired them to tell me what’s wrong with my manuscript and how to fix it. If you have a thin skin, then perhaps you should write for your friends and neighbors and skip the publishing step.

Finding a good and reliable cover designer took me almost two years. Most designers need six months before you can get on their list. The cover is extremely important. It is the first thing that readers see. The imagery and font must grab the reader as they peruse millions of books—and, at first, they only see a thumbnail of your cover. It is a true art to put together effective covers, even down to the minutia that certain genres do best with certain colors on the cover.

Once you have the book components put together, you must find a publisher. I researched and went with IngramSpark for my paperback. They have worldwide reach and a professional product. Initially for my ebook, I went ‘wide’ with Pronoun, who had been acquired by MacMillan and I thought pretty stable. They were very easy to work with and pushed the ebook out to Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Apple iBook, Google Play and Kobo. They went out of business within a year of publishing through them. So, I went ‘narrow’ and published through Amazon’s Kindle, because of their marketing tools.

Prior to your launch date, you must have bloggers, reviewers, etc. etc., talk about your book. I put my first book onto NetGalley, but for me, it seemed to be a negative—one reviewer out of about ten reviewers was, in my opinion, professional. The others seemed to have a strong degree of ‘read rage’ as it were—some of my best trolls came from NetGalley. Amazon reviews tend to be tamer, but oh so necessary. To get onto marketing sites such as BookBub, you must have a minimum number of Amazon reviews.

Marketing for your novel is a requirement through various sites and social media. Creating book trailers, Twitter, Instagram and Facebook posts will become integral in your publishing life. Gathering authors within your genre to form a marketing group can truly expand your reach.

Assembly required. And can you please pass that bottle of wine?

ANDY WEIR: Author of THE MARTIAN takes on the Moon...

Andy Weir rose to fame with the publishing and subsequent film production of his debut novel, The Martian, published in 2011, but, as his dedicated fan base knows, his writing career began much earlier.

Photo credit: Aubrie Pick

Andy was born in 1972 in Davis, CA, a suburb of Sacramento, to a particle physicist father and an electrical-engineer mother. He grew up reading science fiction, and starting at the early age of fifteen, worked as a computer and video game software programmer for a variety of companies.

With a mind fluent in science and an itch for writing, Weir delved into comics, short stories, and other writing projects through his twenties and thirties. His first published work was a short story titled, The Egg, published in 2009, setting him on his path as an author. He developed an online fan base, and though rejected by the traditional publishing industry, Weir persevered with his writing.

The Martian was initially a serialized story published free on his website and drew interest from a burgeoning reader base, including scientists, eager to suggest solutions as to the ‘how’ of a human marooned on Mars. The serial was a hit, and with fan pressure, he self-published the novel on Amazon Kindle for 99 cents, and The Martian quickly rose to the Kindle bestsellers list.

With proven sales, Weir was approached by a literary agent, then picked up by Crown Publishing Group, and the print version of the novel debuted at #12 on The New York Times bestseller list. The Martian film, based on Weir’s novel, was produced by 20th Century Fox, directed by Ridley Scott, with Drew Goddard adapting it into the screenplay. Starring Matt Damon as the affable and self-reliant Mark Watney, the film was released in 2015 to rave reviews—and changed Weir’s life.

Weir’s latest novel, Artemis, is a near future thriller set in a small colony on the Moon at the end of this century, with a female protagonist snagged into a nefarious web of corruption, and launched on November 14th, 2017.

K.E. LANNING INTERVIEW WITH ANDY WEIR:

What are the primary influences in your writing, such as authors you’ve read, or significant events in your life?

I grew up reading my dad’s sci-fi collection. So I read a lot of Baby-Boomer sci-fi despite the fact that I’m a Gen-Xer. So my idols and role models are Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, and Arthur Clarke.

What led you to become an author? Was there a specific epiphany you can tell us about?

I never had any specific “aha” moment. It’s just something I always wanted to do. But I didn’t think I’d be able to make it against all the competition so I went into computer programming instead. I did have a three-year sabbatical where I wrote a book and tried to get it published, but I didn’t get any traction. So I went back to programming and wrote as a hobby. That’s where The Martian came from, and I ended up able to follow that dream after all.

Can you give us some insight into your writing process?

I like to set myself a word-count goal. I know, it’s a beginning-writer thing to do, but remember I really am still a beginning writer. One success doesn’t suddenly make me a wise old sage.

I’m a fundamentally lazy person, so my biggest challenge is motivation. I have to force myself to write and get stuff done or I’ll put it off and put it off. I write in my home office, which means there are all sorts of distractions around that I would much rather do. I’m into woodworking and my garage is just 20 feet away. I have cats that love attention. That sort of thing.

So I make “rules”. Like “No woodworking until I’ve made my 1000 words”. And “No TV or YouTube either.”

The science fiction genre is broad—your writing seems to be more on the traditional science fiction end and not as much on the social commentary/speculative end of the spectrum. Can you discuss this?

I dislike social commentary. Like… I really hate it. When I’m reading a book, I just want to be entertained, not preached at by the author. Plus, it ruins the wonder of the story if I know the author has a political or social axe to grind. I no longer speculate about all possible outcomes of the story because I know for a fact that the universe of that book will conspire to ensure that the author’s political agenda is validated. I hate that.

I put no politics or social commentary into my stories at all. Anyone who thinks they see something like that is reading it in on their own. I have no point to make, and I’m not trying to affect the reader’s opinion on anything. My sole job is to entertain and I stick to that.

To that end, I also don’t talk about my personal political opinions publically. I don’t want readers to even know, honestly. I don’t want that in the back of their minds as they read my stuff.

I totally respect your personal views, but you had also mentioned Heinlein, Asimov, and Arthur C. Clark as influences. Heinlein in particular delves into social commentary in such books as Stranger in a Strange Land. And there are many classic sci-fi novels in which the author creates dystopian universes to comment on the human condition, such as Brave New World, 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale, etc.

Yeah, I didn't really like the political message aspects of those stories. Not that I disagreed with the political point. Just that I didn't like the political points being there at all. Now, those writers are so good they make compelling and addictive stories *despite* the political messaging. But that's often not the case with other stories and other authors.

You're not mis-reading me, though. I deeply dislike social commentary. For instance, as a lifelong Star Trek fan, it's always bothered me that there is a presumed "responsibility" within Star Trek shows to talk about social issues. I just want to watch Romulans and the Federation shoot at each other.

I'm not saying anyone else should hold my view. Many readers select books specifically for their social commentary. There's no "wrong" way to enjoy a book. But in the end, as a writer, I can only do my best to write books that I would enjoy reading. So, for me, that means no politics.

It’s very effective, but why did you choose the first person, journal format to write The Martian?

The Martian required a huge amount of exposition to work, and there’s no way that could happen without humor. I had to have someone explain it in a funny way or it would read like a Wikipedia article. Also, since Mark was alone, there would be no other way for the reader to know what was going on in his mind unless he told them.

Mark Watney’s character in The Martian, reveals a heroism and humanity at the deepest level. How did you develop his character?

Mark is basically me. But he’s the distilled, idealized version of me. He has all the qualities I like about myself and none of my many flaws. And he’s better at all the things I’m good at. He’s what I wish I were.

The thread of exploration and colonialism is common in both The Martian and your new novel, Artemis, which is set in a colony on the Moon. Can you flesh out this theme?

Artemis takes place in the late 21st century, maybe 70 years in our future. The titular city is humanity’s only city on the Moon. I put a lot of work into figuring out why there would even be a city on the Moon and how their economy works. It’s a frontier town with a heavy emphasis on the tourism industry. I tried to be realistic on what kinds of people would be there, and how their society would gel.

Can you give us some background on your new novel, Artemis?

Jazz Bashara has lived in the lunar city of Artemis since she was six years old. She’s a bit on the shady side, augmenting her meager income with smuggling. She gets an offer from a local business magnate to do a very illegal sabotage job and the payoff is too big to ignore. Of course, things go wildly awry (wouldn’t be a heist story if they didn’t) and Jazz finds herself in mortal danger as the very powerful people she angered come after her.

How did you develop the character of Jasmine Bashara, the protagonist of Artemis?

I came up with the city itself first. The economy, the technology to make it, how it was built, etc. After that, I set about inventing a story to take place there. In the first story idea I had, Jazz was a very tertiary character. I needed a smuggler so I picked a fairly random country for her to be from (I ended up with Saudi Arabia) and rolled with it. Jazz was kind of a funny side character but that was it. However, that story concept didn’t work out well and I abandoned it.

Then I came up with a completely different story idea, and this time Jazz was more prominent. She was still a secondary character, not critical to the plot, but was interesting. That story also fell flat.

I realized that the most likable thing about both of those concepts was Jazz herself. So I took a stab at writing a story that revolved around her personally. And that’s what became Artemis.

Since the launch of Artemis, there have been some critical reviews of your main character, Jazz. Can you comment?

Jazz is a complex, very flawed person, who often makes bad life decisions. It's a fine line you have to walk when making an anti-hero. You need them to be "bad" but not so bad that they lose the audience. It's easy to alienate the reader from the protagonist if you do it wrong. Many readers had a hard time rooting for her. I can understand that, and I'll learn from the experience. I pay very close attention to the feedback I get - I'm always trying to get better at what I do.

However there is a minority of people who view everything through a lens of social issues. And they're more focused on Jazz's gender then they are in any other part of the story. Many consider it wrong of me not to focus on social issues in the book - as if simply having a female lead means I had some responsibility to make it about her gender. That's not how I write, so I don't think there was anything I could do for people who want that kind of story.

And finally, there's feedback about my portrayal of a woman. It was a challenge for me to write a female protagonist, and I did my best. But there are certainly going to be places where it doesn't quite ring true. Some critiques of the book point out those parts and I try to learn from them. However, there are also female readers who assume Jazz should think and act exactly like they do, and get mad when she doesn't. The challenge is separating the legitimate critiques of the female voice from people who can't accept that a woman who grew up on the moon in the late 21st century might have different attitudes than a contemporary American woman would.

How has your success as an author changed your life and what’s next on the horizon for you?

Well, I have a lot of money now. So I moved into a nicer house. :)

But other than that, not a lot of change. I’m still the same me, with the same friends and hobbies. I plan to continue writing as long as people keep buying my books. I would love for Artemis to become a series. We’ll see if it’s received well enough to warrant sequels.

Best of luck, Andy!

My sincere thanks to Andy Weir for graciously agreeing to my interview and to Sarah Breivogel of Penguin Random House for all of her help!

K.E. Lanning, Author of

THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee and Listen to the Birds

This article can also be found on FUTURISM

Speculative Fiction: What the HELL is it?

Thomas More and Utopia

As in any advent of a new species, the birth of the science fiction genre led to an evolution of novels ranging from Thomas More’s Utopia to Andy Weir's THE MARTIAN.

However, when a genre becomes so diverse that readers are uncertain as to whether the book they are interested in is a high tech detective story set on a spaceship or a deep dive into the political shenanigans of a warped future society, then perhaps it is time to shake up the genre for clarity. By some definitions, speculative fiction (spec-fi) is characterized as an umbrella description of the broad spectrum of science fiction and fantasy, but the term first appeared as a genre reference in 1947 in an editorial essay, On the Writing of Speculative Fiction, by the venerable sci-fi author, Robert A. Heinlein.

Robert Heinlein

An excerpt from his essay:

There is another type of honest-to-goodness science fiction story that is not usually regarded as science fiction: the story of people dealing with contemporary science or technology. We do not ordinarily mean this sort of story when we say "science fiction"; what we do mean is the speculative story, the story embodying the notion "just suppose—" or "What would happen if—." In the speculative science fiction story, accepted science and established fiefs are extrapolated to produce a new situation, a new framework for human action. As a result of this new situation, new human problems are created—and our story is about how human beings cope with those new problems.

A major influence in my own writing, Heinlein wrote social commentaries such as Stranger in a Strange Land and I Will Fear No Evil. In The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, Heinlein writes a chilling account of a revolt in a penal colony on the Moon, and contributes the formulation of his heroic archetype to author Ayn Rand’s protagonist, John Galt, in Atlas Shrugged, known for its political views.

Heinlein was a mentor to the great Ray Bradbury, one of the quintessential science fiction authors, yet his novels such as Fahrenheit 451 are closer to the speculative fiction end of the sci-fi genre. In a 1982 essay, Bradbury wrote, "People ask me to predict the Future, when all I want to do is prevent it."

Ray Bradbury

The sci-fi author, Octavia Butler, explores the human condition via time-travel in her novel, Kindred, in which her protagonist, a young African American woman, Dana, is transported from modern California to the pre-civil war South to save a young white boy from drowning. As the story progresses, Dana is swept back and forth in time, seeing the boy harden into a slave master as he grows older, and experiencing the way slaves are conditioned to bondage by their cruel subjugation.

Octavia Butler, photo credit Leslie Howle

In a recent interview, I asked the renowned author, Margaret Atwood, about the term science fiction and the confounding breadth of the genre. Atwood believes her work, such as The Handmaid's Tale, and other authors utilizing social and/or political commentary or examining the vicissitudes of humanity, should be termed speculative fiction, rather than science fiction.

Margaret Atwood in K.E. Lanning’s 2017 Interview [updated with the Emmy Awards]:

…We could just call it [sci-fi and speculative fiction] two different things. We can call it apples and oranges. Apples take place on other planets and have spaceships in them, and oranges take place on planet Earth and have to do with what we're doing here now and only the technologies that we already have got our hands on. There's a difference in kind between those two things. I know that when I go to the sci-fi shelf, I expect there to be other planets. To avoid disappointment, because when I buy a package of bran flakes, I want there to actually be bran flakes in the box—to avoid disappointment, I feel they [spec-fi] should be called something else.

The designation of speculative fiction, focusing on social commentary rather than technology, regardless of the novel's time frame, could encompass literature such as Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, 1984 by George Orwell, The Lathe of Heaven by Ursula K. Le Guin, and the WOOL Omnibus series by Hugh Howey—all speculating on the human condition within dystopian, apocalyptic, or post-apocalyptic worlds in order to highlight the existence—and the danger—of political corruption and social crises.

For readers’ sake, is it time to consider whether speculative fiction should be a separate genre, or at a minimum, have equal billing to science fiction and fantasy—to elucidate what’s between the covers of that book?

K.E. Lanning, author of speculative fiction: A Spider Sat Beside Her, and The Sting of the Bee [2018 release]

This article was first published on FUTURISM, October 19th, 2017: Speculative Fiction: What the Hell is it?

The original Margaret Atwood 2017 interview and the trailer for the Hulu series is available online at FUTURISM. This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

Margaret Atwood: 2017 Interview & The Handmaid's Tale at the Emmys

Margaret Atwood by photographer Liam Sharp

Margaret Atwood is a poet, a novelist, and an inventor. She was born in Ottawa, Canada in 1939 to Margaret (maiden name Killam), a nutritionist and to Carl Atwood, an entomologist. With her father’s research in entomology, her early childhood was spent deep in the forests of Canada. Always a voracious reader, she knew by the age of sixteen that writing would be her vocation. Atwood graduated in 1961 with a Bachelor’s degree in English from Victoria College in the University of Toronto, and in 1962, received a Master’s Degree from Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA.

In 1961, she won the E.J. Pratt Medal for her book of poems, Double Persephone. Atwood has also been a writer of feminist works such as The Edible Woman, published in 1969.

In Atwood’s speculative fiction (literary science fiction) novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, published in 1985, she skillfully delivers a terrifying tale of a female protagonist caught in a wretched social and political nightmare within an authoritarian theocracy set in a future New England. In 1987, she won the first Arthur C. Clarke Award for this stunningly written novel.

Atwood’s latest novel, MADDADDAM, was published in 2013, completing the trilogy started by Oryx and Crake, in 2003, and followed by The Year of the Flood in 2009.

On par with Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, and George Orwell’s 1984, Atwood's poetic prose is timeless, dissecting the accepted norms of society, politics, and the human condition. In a quote from The Handmaid’s Tale, Atwood’s protagonist Offred says, “We have learned to see the world in gasps,” a stark warning to never become complacent in our freedoms.

Margaret Atwood is an extraordinary person—a thinker and a story teller, using her literary talents to challenge our beliefs, carrying us on an allegorical ride through dystopian worlds facing environmental disasters and societal extremes—revealing the fragile nature of our humanity.

Hulu's The Handmaid's Tale

Hulu's new series, adapted from Atwood’s classic dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, is set in the near future when the totalitarian society of Gilead has come to power in the northeastern United States. Facing environmental disasters and a plunging birthrate, Gilead is ruled by a twisted fundamentalism in its militarized “return to traditional values.” As one of the few remaining fertile women, Offred (Elisabeth Moss) is a Handmaid in the Commander’s household, one of the 'caste of women forced into sexual servitude as a last desperate attempt to repopulate the world. In this terrifying society, Offred must navigate between Commanders, their cruel Wives, domestic Marthas, and her fellow Handmaids – where anyone could be a spy for Gilead – all with one goal: to survive and find the daughter that was taken from her.

Photo credit: Hulu

Hulu's production of The Handmaid's Tale was a HUGE WINNER at the 2017 Emmy Awards:

Outstanding Drama Series, Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series [Elisabeth Moss], Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Drama Series [Ann Dowd], Outstanding Writing for a Drama Series [Bruce Miller], and nominated for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Drama Series [Samira Wiley]

K.E. Lanning Interview with Margaret Atwood April 10th, 2017 [text]

K.E. Lanning: It's really an honor to speak with you—I appreciate your time.

Margaret Atwood: Thank you.

I'd like to start at the beginning. In reading your bio, your father was an entomologist, so you spent a lot of your early years with your family in the forests of Canada. Why don't you tell us a little bit about your childhood and any significant events that shaped you as an author.

Well, you never know these things. It was a reading family because there was no electricity and we were not getting any TV. In fact, nobody in the late forties was getting TV much at all yet. Radio; we could get Russia on shortwave, for what that was worth. Basically, it was reading, drawing, and writing.

I was an early reader, and there was never a book around that I was told I couldn't read. That would include everything from detective thrillers to biology textbooks, to sci-fi, because of my dad, as a scientist, got a kick out of sci-fi. He had early classics around, such as Karel Čapek, Brave New World, and HG Wells.

I myself continued on in the fifties with Ray Bradbury as he published, and John Windham also as he published.

Recently, I did a list of dystopias for Omnivoracious, on Amazon and Goodreads.

As kids, we were into rocket ships and other planets, and all of those things that I suppose really started with Flash Gordon and A Princess of Mars, War of the Worlds, those kinds of books in the early part of the century. That turned into Weird Tales and other magazines of the thirties.

We had the funny papers. On the weekend, there would be a supplement and a lot of well-loved comics. It was also the age of comic books in the late forties—the golden age of superheroes. Not just Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman, and Captain Marvel, but a whole bunch of other ones.

It was such a great golden age of [comics].

That's what people think now, but at the time they just thought it was bad for you, and that children shouldn't read them. That's when the comic’s code came in, but unfortunately for them, it only applied to colored comics, and you could still get the crime and horror in black and white.

They felt it wasn't as bad in black and white?

I don't know what they thought. It was actually worse. It didn't look as fake.

I was also reading that by the age of 16, you had already decided that writing would be your profession.

Vocation. There wasn't any chance of it being a profession, a profession for which you got paid. This as Canada in the fifties, you have to understand. You didn't expect to actually make any money out of it, so I had a brief flirtation with something called Writer's Magazine in which they listed in the back all of the places where you could sell things to magazines. The thing that paid the most was true romance, so I thought maybe I would write true romance in the day, and then in the evenings I would write my literary masterpieces, but that did not go very far because I wasn't actually up to the task. I could not do the vocabulary, which included at that time a lot of asterisks, and sentences like, and then they were one..... That I could not do. Things happened on sofas in those magazines.

These would be the stories in which there would be two male suitors, one would work at a shoe store and the other would have a motorcycle, and you just know what happens then. Wuthering Heights, only in modern setting.

You've gone over some of the writers that you enjoyed as a kid, but I was wondering, are there any other authors that you consider primary influences to your writing?

Apart from the fact that I read all of Edgar Allen Poe at too early an age—it was in the children's library section because it didn't have any sex in it. Who made that decision? I understand now because I just did an introduction to a book of his. Ray Bradbury did the same thing—Poe was an early influence. I don't know whether you've read all of Poe, but some of it is terminally gruesome.

I know that in some of your discussions you've talked about having elements of environmentalism and humanism in your work. I was just curious [on your thoughts].

I would say environmentalism I grew up with—it's just part of biology. I'm not sure what humanism mean? I've never quite known.

The definition of humanism changes through history. In some definitions, it's sort of an acceptance of you as a human and accepting everything about being a human, and not necessarily being obsessed with religion to the point of conflict with our humanness.

I'm a strict agnostic, by which I mean there's a difference between what you can know, which has to do with the physical world, and what you can't know. What you can't know remains an open question. Those things are a matter of faith, and there's just a difference between faith and knowledge.

Yes. I think that when you have a religion that carries a club to beat the human out of you, then there's something wrong with it.

But that's just one use of religion. It's a narrative subset, by which I mean you can tell by looking at what kids do under the age of three or four what's in the human package. We know that language acquisition, and music and rhythm, and storytelling, and visual imagery—kids will do that very readily. They just pick it up.

A narrative, something that only human beings do, started pretty early to tell stories about where did we come from and what happens to us in the future, and Rover the dog will never do that. Rover the dog will never say, as far as we know, what was the origin of dogs, where did dogs come from, and will never say what will happen to me personally, Rover, when I die. But human beings do that all the time.

There are all of these different narratives, and there have been very many of them, and because there have been very many of them, it's no good saying to people you shouldn't do that because it seems to be something that people do. If there shall be religion, which it appears that there shall be, let's hope that it is a good one, and not used as a hammer.

You probably say, well they're [ideologies] are a form of religion, or you could say that religions are a form of ideology, whichever you prefer, but when there is a belief system that gives you the permission to kill other people who don't share it, that's the negative aspect. But let us not be blind to the fact that there are positive aspects.

It's one of the things that sci-fi does all the time, makes up other religions.

Speaking of science fiction, I was interested in a discussion that I read that you were talking about the term science fiction as a genre, and the difficulty with that, and you feel like that what your work is speculative fiction.

Or we could just call it [sci-fi and speculative fiction] two different things. We can call it apples and oranges. Apples take place on other planets and have spaceships in them, and oranges take place on planet Earth and have to do with what we're doing here now and only the technologies that we already have got our hands on. There's a difference in kind between those two things. I know that when I go to the sci-fi shelf, I expect there to be other planets. To avoid disappointment, because when I buy a package of bran flakes, I want there to actually be bran flakes in the box—to avoid disappointment, I feel they [spec-fi] should be called something else.

I agree. I've had definitely difficulty with that myself. I think it's really more, from what I've been able to tell, agents and publishers that are more interested in keeping it within a genre to a certain extent.

As booksellers, they want to know what shelf to put it on. Which is annoying—Ursula Le Guin has quite a lot to say on the subject and I would agree with her that there are not bad genres, there are only bad books.

Margaret, one of the things I was really interested in is the fact that you're both a poet and a novelist. Really, your poetic prose is just stunning. I was wondering if you could just discuss a little bit your journey as a writer.

I don't know whether I have one. I'm so old that there were no creative writing schools.

I think Iowa had started, and in the early sixties one at the University of British Columbia had started, but that was it. We were not encouraged to think in terms of my journey as a writer. We were not at all encouraged in that direction. We were encouraged, if anything, if you were in academia, encouraged not to let on.

People a generation before mine had done things like gone to Paris. In the thirties, people would go to Paris. People of my generation were pretty much led to understand, and this is Canada in the late fifties, that if you wanted to be an artist you needed to go to New York or London. If you were from Quebec, you needed to go to Paris.

Being perverse, I thought maybe I would go to Paris and live in a garret, drink absinthe, smoke, and get TB, and write masterpieces and work as a waitress, but that didn't happen. Although I did later work as a waitress.

It was not about my journey as a writer. It was about how do I support myself if I want to do this? That was what it was about. Then do you get a job that has something to do with writing, in which case you might use up all your writing energy doing that job, or do you get some other job that is not related? People have done both, like working in a bank and being a real estate agent or something.

In my generation, in the sixties in Canada, there weren't very many women writers, and writers were told things by other writers such as, in order to really understand the world, you have to be a truck driver. Except for me. As far as I know, they're not hiring girls yet. Anyway, I can't drive, so it was like that.

I think my journey as a writer consisted of not doing what other people told me I should do.

You really craft your characters very well, and I don't know if you could comment a little bit on how you're approaching your character development.

I think that people in sci-fi are people. Maybe you should try to make them as much like people as possible, unless they're of course an altered life form, in which case you make them like that. I don't think there's any big mystery to it. There was an age of sci-fi, I guess hard rocket ship sci-fi, that I wasn't terribly interested in. I was always more interested in people-centered stories, some of which were just pretty much fantasy under another name. They could all be classed as wonder tales, things that are not going to happen in real life. Under that huge umbrella you could put vampire stories, and werewolf stories, and Frankenstein, though we're getting a bit closer to that, Frankenstein and R.U.R (Rossum's Universal Robots) and all of them, you can call them wonder tales, but they do deal with age-old motifs. I think that a lot of sci-fi got its main stories from mythology.

That's a good observation.

I'm not alone in thinking that. It's not an original thing with me.

One of your extraordinary books is The Handmaid's Tale, which was made into a film in 1990, and now Hulu has developed a series based on that novel, releasing on April 26th. I'm just curious how you feel about your work being adapted to the screen and how involved you've been in the process.

I worked in film and television in the seventies quite a bit, so I know the pitfalls and challenges, and in what ways a novel is not the same as a film or television. Right now we're in an age in which the well-produced series has really carved out a chunk, and it allows you to explore a longer work in depth, and follow characters in ways that you would not be able to do in a 90-minute film.

Whenever a new platform comes along, there's a huge burst of creativity as people explore it and build it out, and that is certainly happening right now.

I saw the trailer, and it looks really interesting.

Yes. I think in my opinion, it's pretty strong. If we're letting me be less Canadian about it, it's very strong.

I had an American writer friend who came up here and he said, they don't like my book. I said, they loved your book. He said, how can you tell? I said, the thing is that ‘not bad at all’ in Canadian is the equivalent of American, ‘best thing since sliced bread’, ‘stupendous’, ‘magnificent’, ‘never been equaled’. It means the same.

You have to have the Canadian to American translator?

Yeah. I think some of the poor Americans need it, whereas the Canadians, of course, if they go down there, they think they've been elevated to the status of a god.

Speaking of that, you are a real icon of the literary world, and I was just curious, what do you feel is your legacy?

Are we talking about me being dead now? Is that the subject?

We're trying to get the words down before then.

You never actually know until you are dead, and you probably aren't going to know that either, but other people will know.

Legacies come and go, because everybody is always in the present moment, so it's a bit presumptuous to say that you will have a legacy that will be the same forever and ever because it won't be. Typically what happens when somebody fairly well-known dies is there is a bust of interest in their work, and then it either sinks into oblivion, never to be seen again, or it sinks into oblivion and then makes a comeback a little bit later.

Is there any message that you have tried to put forth [in your writing]?

How we were taught poetry in high school, we were taught what is the poet trying to say, which meant that we thought, why do they have to spend all those words if what the poet was trying to say was war is hell? Why couldn't they just blurt it out instead of putting us through a sonnet?

I don't go in for telling the reader what the message is, because everybody reads in an individual way, and takes away something that has something to do with what they brought to it, or let us say that the reader is the violinist of the book. Every reader is reading the same book, but each interpretation of that book is going to be different, so I strenuously avoid telling the reader what I prescribe the message to be, since my job as a writer is making a world that is as complete as I could make it.

I did write a book called originally Negotiating with the Dead, but the publishers were put off by the dead word and changed the title to A Writer on Writing. Squeamish, aren't they? In the beginning, in the introduction I said, first of all, I tried to figure out what all of these writer's motives were, dead writers and living ones, and it was everything from to justify the ways of God to man, or to get back at the people who were mean to me in high school, or it could be both. I think my favorite was a Czech writer who said, “I want to make a boudoir so that the reader can go into it and have fun.” I thought, that's no good.

There's a big leap between a boudoir for fun and to justify the ways of God to man. Instead, I asked myself, and dead and living writers, what's it like to go into a book? I was looking at the beginnings of things, and everything from, I was wandering in a dark wood to Virginia Woolf saying writing a novel is like going into a dark room and holding up a lantern which illuminates things that were already there. All of the answers had something to do with going into the dark and illuminating something.

That's what writers do, in my opinion. You go into the dark, you go into an unknown, which is the thing you're trying to write, and then you attempt to illuminate it and bring something back into the light.

That's wonderful. I love the way you say that.

I believe I heard that you're writing a new novel. Is that correct? Is that what's next on the horizon for you?

I'm very cagey about saying what I'm doing. Once upon a time I did say what I was doing, and then, of course, I didn't do it, and I got an endless number of questions. But you said you were going to do that, why didn't you do it? There's no point saying what you're going to do until you've actually done it. For the same reason, I never actually tell my publishers what's going to be in my next book, because they would probably make horrified sounds. They usually want you to write the book you just wrote.

Margaret, I really appreciate you taking the time to speak with me, and best of luck!

My sincere thanks to Margaret Atwood for graciously agreeing to my interview, and to Lucia Cino, Melinda Casey, Lauren Thorpe, and Phoebe Larmore for all of your help.

K.E. Lanning, Author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee and Listen to the Birds

The interview and the trailer for the Hulu series is available online at FUTURISM. This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

CIXIN LIU

The hottest sci-fi writer in China takes on the world...

Photo courtesy of Tor Books

Liu Cixin [writing in English under the name, Cixin Liu] is a science fiction writer from China; a nine-time winner of the Chinese Galaxy Award (Chinese Hugo) and the Xing Yun Award (Chinese Nebula), and the first Asian to win a Hugo Award, in 2015, for his work, The Three-Body Problem (translated by sci-fi author, Ken Liu, and published by Tor Books.

So who is Liu Cixin? He was born in 1963 in Yangquan, China, during that country’s Cultural Revolution—a major influence in his life. His parents worked in a mine in Shanxi, but sent Liu to live in his ancestral home in the Henan province to escape the violence in the country. Liu was educated at the North China University of Water Conservancy and Electric Power, graduating in 1985, and then worked as a computer engineer. [primarily sourced from Wikipedia]

He’s an engineer by training, but what was the spark for Liu to write speculative science fiction?

As a scientist, a longtime reader of science fiction, and now myself a science fiction author, I embrace the idea that science and art are two sides to the same coin. In Liu’s novels, physics becomes poetry and his characters reveal vulnerable souls, lost in a shifting world they can’t truly grasp, but who remain determined to be true to themselves.

His characters travel through a procession of spectacular worlds, strung like pearls along a silk cord, harkening back to the intricate creations built by sci-fi writer, Arthur C. Clarke. Josh Rothman of The New Yorker wrote a lovely article on Liu Cixin: http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/chinas-arthur-c-clarke

Through his writings, Liu Cixin reveals an amazing mind, using science as both a physical and creative force, imagining worlds in which humans are never sure where the fate of the universe will leave them.

Cixin Liu Interview with author K.E. Lanning

You were born during the turbulent time of the Cultural Revolution in China. Your parents worked in the mines of Shanxi, but you were sent to live in the Henan province to escape the violence. Can you tell us about growing up in that difficult period in China and how it affected you as a writer?

As a child, I witnessed a great deal of violence and persecution as well as social unrest during The Cultural Revolution. These are all mass movements, which, at some point, made individuals uncontrollably crazy, just like Gustave Le Bon in The Crowd as he was described in the book. This experience has made me understand the complexity of human nature and society—I’ve realized that the future of human civilization is also full of danger and uncertainty. Such understanding is manifested in my science fiction novels like The Three-Body Problem.

Do you feel that you are a driven person and what specifically drives you?

I was quite curious about the unknown world and was full of yearnings for the vast universe, and it was this wonder and desire that drove me to write science fiction. I’ve tried to describe the relationship between man and nature and the universe, using imagination to expand my existence.

Physics is the elemental language of the universe and you weave it into your writing like poetry. Can you discuss your love of physics and the role it plays in your works?

Physics is the science to understand the fundamentals of the world and it explores the deepest mysteries of nature and the universe. The world described by modern physics has already moved far beyond our common sense and intuition, even beyond our imagination, and this is, of course, the richest resource for science fiction. I’ve tried to turn the magical world as demonstrated by modern physics into vivid stories. Most of my stories were based on and imagined along the lines of physics and cosmology.