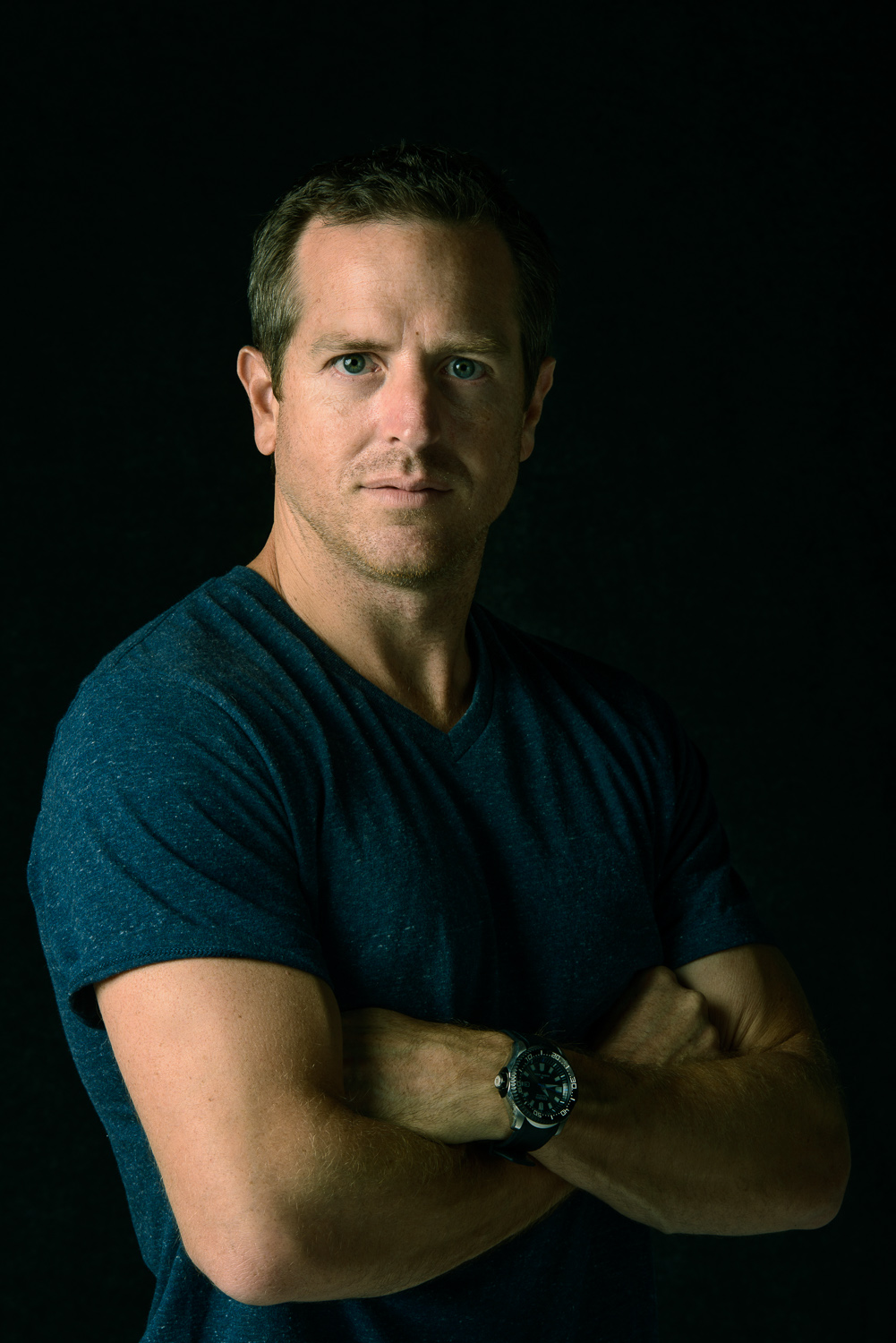

Hugh Howey

Still a vagabond after all these years. . . .

Hugh Howey is an author of science fiction and whatever else he wants to write about—as an independent author—he controls his writing career.

Born in 1975, Hugh grew up reading and sailing, navigating away from a traditional childhood of spiritual and physical boundaries. After a stint in college, where he studied English and physics, he dropped out to renew his connection with the sea. Marriage brought him to dry land once again, where he pursued his other passion—writing.

With his breakout novel, WOOL, Hugh Howey

became an international bestselling author, leaping onto the New York Times best seller list. The complete trilogy of WOOL , SHIFT, and DUST have been published, completing the omnibus series.

I was fortunate to catch Hugh for an interview—in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Hugh Howey Interview

by K.E. Lanning

I read in an interview by John Biggs during which you described yourself as a vagabond, or I might describe it as a “free human” in a sense. Can you flesh that out?

The only way I could sit still as a kid was with a book in my hand. If my body wasn’t moving, my thoughts needed to race. I guess not much has changed. I like the novel in life (pun intended). Being in one place too long makes time start to flow quicker and quicker, until years have zipped right by.

I used to think no one place could ever feel like home, which is why I thought of myself as a vagabond. But I’ve learned over the years that every place feels like home to me. I’ve always been lucky in this way: I can insert myself into almost any situation or conversation and feel perfectly at ease. When I started traveling on book tours, every country and state I visited felt like a place I could settle down for years. This doesn’t make me want to settle, though. It makes me want to see the next place that I could call home.

Do you feel that you are a driven person and what specifically drives you?

No, I feel quite lazy. Maybe that’s because my ambitions are greater than my drive. All I can think about are the books I haven’t written and the places I haven’t seen. It feels like I could do so much more, but I’m too content with my life to push myself any harder. I’ve always had this feeling of wasted potential, mixed with a blissful satisfaction with my life. I think I just feel too lucky to berate myself for not having done more.

Do you think your love of the ocean is, in a way, a form of escapism into a parallel universe?

I love the ocean the way I love a blank canvas. This is something I thought about a lot before answering. You have to picture where I am right now: I’m sitting on a sailboat, surrounded by the blue Pacific, halfway between Panama and the Galapagos. There isn’t another boat for fifty miles in any direction, and no land for hundreds of miles. Looking around, and pondering your question, all I can see is the potential around me. The emptiness can be filled with whatever you like. I could sail east to Ecuador, or north to Cocos, or south to the horn. It’s like a new Word document, which can be any of an infinite number of novels. Or a Saturday morning with no plans. It makes you breathe more deeply, that kind of freedom. And exhale more easily.

What are the primary influences in your writing, such as authors you’ve read, or significant events in your life?

The events of 9/11 have impacted almost everything I’ve ever written. I see it in every story, even when I don’t plan on it being there. I think I’m still working through things from that day and the days immediately after.

Serious writing takes not only a story to tell, but the craft of writing to tell it well—can you comment on your journey as a writer?

It’s a journey I’m still on. I don’t think of myself as a very good writer, not yet. But I’m still young. I like to think I have a great work in me somewhere. Maybe with another fifteen novels, I’ll find it.

I think of writing as a sport. You fall in love with a sport as a spectator, and it makes you want to play yourself, and perhaps get better, and maybe turn pro. All writers begin as readers. The more you read, the more you prepare yourself for this. But then you have to play game after game to improve. Revising a single novel to oblivion doesn’t make you a better writer. You have to finish and start over again, and do this dozens of times, and never lose the zeal for it.

Right now, I’m a guy who comes off the bench. I’ve had a game or two where a few buckets fell in a row, and some of that is practice and a lot of it is luck. But if I keep at it, there will come a time when I rely less and less on the luck. When I get good at this.

I know you write all types of genres, but since this is an interview for a Sci-Fi audience, what drew you to write a dystopian science fiction series?

Dystopias are such powerful tools. They allow satire, and warning, and hope. There’s no better way to comment on the trajectory of the present than to point out where we think these string of days might land. That’s what the dystopian writer gets to do. She’s the outfielder racing for the warning track, glove outstretched, seeing where the events of time are taking us before anyone else.

The SILO series is both political and social—in the manner of the books that I was drawn to as a kid, and in fact, my novels are similar in vein. What do you wish to convey with your dystopian ‘message in a bottle’, i.e. silo [pun intended]?

The main point of this series is that we’re all victims of our beliefs in human nature. Roughly half of us see humanity as deeply good and worthy of being completely free. The other half sees humanity as deeply flawed and requiring restraint. Jean Jacque Rousseau wrote about the first perspective; he saw humans as “noble savages.” Thomas Hobbes wrote about the latter perspective; he thought we needed a “leviathan” to keep us in check.

In my novel WOOL, you have a heroine who subscribes to the noble savage view, and you have a pretty bad dictator who subscribes to the leviathan view. A careful reading of the book will reveal the flaws and correctness of both viewpoints. There is another character in the book who is torn between the two, a character of compromise. This is the rare viewpoint among us. Few subscribe to such nuance. But I believe it’s where our salvation lies.

One thing I really enjoyed in reading WOOL was the realistic depth of the characters within the confined world of the silo. How did you create the characters in the novel and did they go through any metamorphosis as you wrote?

Of course. Every good character in fiction should change. And they should all be complex and layered. They shouldn’t even be consistent in their beliefs and actions; few people are. Most importantly, they should have a reason for what they are doing at any time. Especially the “bad guys.” Most people we consider bad in the real world have an internal justification for what they’re doing. They aren’t evil for the sake of being evil, and we do ourselves a disservice to simplify people in this way. There’s no way of helping them (or ourselves and each other) without understanding them.

You made a decision to indie publish and are one of the success stories leading the charge in that direction and away from traditional publishing houses—any comments on this?

Oh, I could do an entire interview on just this topic. I’m a firm believer in this: Literature should serve the reader and the writer. Those are the two parties who matter. Everyone else should hardly register. That means bookstores, libraries, publishers, retailers, etc. It should always be the reader and writer that we consider first.

I’ve found in my time as a bookseller, consumer, writer, and publisher that this is rarely the case. We worry about bookstores closing, and library attendance, and publisher margins, and stock prices. What we barely talk about is how to get more people addicted to reading, how to get more people to believe in themselves as writers. What we do instead is beat down students with the “classics” until they hate anything in the shape of a book. And we beat down writers with the odds of making a living until they no longer love the pure joy of the craft. This is so backwards it hurts.

Writers should be encouraged to publish. People should be encouraged to read what brings them joy. That means a lot more science fiction and romance in the classroom. Less stigma about what is read and more stigma over the fact that so few love to read. Less stigma about how we publish and more stigma over whether we give it our all.

Indie publishing is a celebration of different voices and too-long stigmatized genres. It is so far and away superior to traditional publishing, that all we can do is point out the many ways publishers need to catch up and try to help them do so.

There are multiple novels in the science fiction genre that were self-published and then broke out and several that were optioned as films, such as Andy Weir’s THE MARTIAN. Do you believe there is something about the genre that is not easy for agents and publishers to pick up?

Yeah, too many agents and publishers don’t like science fiction. They care less about what readers really want and care about what they want as individuals. That wouldn’t be a problem, except that their individual tastes are in the minority and far too narrow.

I noticed this in my years of working in bookstores. Anything from the genres that was considered great was moved into the literature section. Frankenstein, The Handmaid’s Tale, 1984, Brave New World. Others were called “classics,” like [novels written by] Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. Retailers and publishers pluck all the best genre works and decide that they can’t be genre, because genre sucks and these things are good. It’s a form of the fallacy called Begging the Question, where you frame the question to match the answer you’re seeking.

What self-publishing has done brilliantly is expose the gap in the publishing industry’s understanding of readers’ tastes and those actual tastes. That gap is so freaking enormous that more works are now sold by self-published authors than all of the 5 major publishers combined. That’s how myopic their views have been and how inane their business acumen. And they still don’t seem to care. My hope is that they will learn to.

I believe you publish ebooks through Amazon, but publish your hard cover copies via Random House?

I publish with Random House in the UK and with Hougton Mifflin Harcourt in the United States. Plus over 40 other publishers in 40 other countries.

It’s fantastic that WOOL is in pre-production adaptation as a film by Nicole Perlman, out of 20th Century Fox. How do you feel about seeing your work adapted to the screen? How involved are you in the adaptation of the screenplay? Just curious, do you have any specific actors you would like to see for the main characters?

I don’t involve myself in the process. I read the scripts and comment on them. My view is that nothing will get made from any of my works, that all I’ll ever see is options and a lot of talk and excitement from production teams, and then nothing more. I’m totally cool with that. I’ve got too many friends who got their hopes up and were let down to fall into that trap. The day someone rips my ticket in half and I’m smelling popcorn is the day I let it start to sink in.

Are you handling the rights for the film or are you going through a film agent?

I have one of the very best film agents in the business, Kassie Evashevski. She knows better than to let me handle anything.

What’s next on the horizon for you?

The Galapagos Islands. They’re 500 nautical miles away. Should be there in less than three days. After that, who knows? The ocean is a great big empty canvas.

My thanks to Hugh for graciously taking time out of The Wayfinder

voyage to do this interview—I appreciate it!

Smooth sailing!

K.E. Lanning

Also available on FUTURISM: In the Author's Universe: Interview with Sci-Fi Author Hugh Howey