Hot News for Hot Times...

News Flash for the masses huddling in A/C on this July day of 2024 with the Misery level in triple digits…

Posters for In the Wilderness and Where the Sky Meets the Earth

My short screenplay, In the Wilderness (a scene out of my Where the Sky Meets the Earth miniseries) is a TOP FINALIST in the Richmond International Film Festival!! And to sweeten the pot, the pilot screenplay for the miniseries, Where the Sky Meets the Earth, was also honored as a Semi-finalist in the Richmond International Film Festival -- WOOHOO! Many thanks to the judges, RIFF, and especially my awesome critique group, Virginia Screenwriters' Forum!!!

AI has no soul...

AI is a double-edge sword—it will improve productivity, and if kept in that lane—will benefit humankind. But a creator of true art? Not so much, because the truth of it — AI has no soul. It can mimic humans, but AI has no human-based instinct, no hormones driving it passionately toward love or hate. By drawing from a million flecks of old thoughts stashed on the internet, it can daub a painting, pen a derivative novel or a formula screenplay, but in the end will humans really care? Did AI draw in a breath at the sight of a lovely bloom on a spring walk? Or shiver at a first kiss?

As I finished my epic journey through Marcel Proust’s À La Recherche du Temps Perdu or In Search of Times Lost [published between 1913-1927], written as a fictional auto-biography, I came to a poignant section as he contemplated his own writing career, grappling with the concept of human context and perception that is unique to each individual. As I read it, it seemed, incredibly, to talk of our current conundrum with Artificial Intelligence.

Marcel Proust, by photographer Otto Wegener

Excerpt from a section of ‘In Search of Times Lost,’ [English translation 1922-1931]:

“…was not nature herself a beginning of art, she who had often allowed me to know the beauty of something only a long time afterwards and only through something else—midday at Combray through the sound of its bells, the mornings at Doncières through the hiccoughs of our hot-water furnace? The relationship may be uninteresting, the objects mediocre and the style bad, but without that relationship there is nothing. The literature that is satisfied merely to ‘describe things,’ to furnish a miserable listing of their lines and surfaces, is, notwithstanding its pretensions to realism, the farthest removed from reality, the one that most impoverishes and saddens us, even though it speak of nought but glory and greatness, for it sharply cuts off all communication of our present self with the past, the essence of which the objects preserve, and with the future, in which they stimulate us to enjoy the past again. But there was more than that, I reflected. If reality were merely that by-product of existence, so to speak, approximately identical from everybody—because, when we say “bad weather, war, cab-stand, brightly-lighted restaurant, garden in bloom,” everyone knows what we mean—if reality were that, then naturally a sort of cinematographic film of these things would be enough and the ‘style’ or ‘literature’ that departed from their simple theme would be an artificial hor d’oeuvre.”

Proust writes that, as an adult, he eats a madeleine cake and dunks it in tea, and is reminded of a vivid childhood memory of the first time he had tasted the cake dunked in tea. These “precious fragments” (term coined by Margold Linton) or involuntary memories can be both pleasant and terrible, and thus he captures these bits of memories within his most famous work.

Proust continues:

“…I perceived that, to describe these impressions, to write that essential book, the only true book, a great writer does not need to invent it, in the current sense of the term, since it already exists in each one of us, but merely to translate it. The duty and task of a writer are those of a translator.”

I believe that Proust was asking a deeply fundamental question—what makes the exquisite words of a line of prose or poetry, a cinematic masterpiece, or a work of art so compelling? It’s not the words or the images in front of us—it wells from the emotions and contextual impressions of our individual past—the joys, the sorrows—the highs of love and the depths of grief—that we’ve experienced in our own lives.

The tsunami of AI is upon us, but we mere humans must not forget that AI is a tool and not a god or super being. At the end of the day, we might well shrug at the bright lights of AI and mumble, “Who cares about the pretty, but sterile pictures AI paints?” And, as beings born of flesh and blood, we’ll go on living and loving like… humans.

How The Crypto Cookie Crumbles…

Review of Michael Lewis’s Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon

Michael Lewis’s Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon delves into the personality of Sam Bankman-Fried, founder and CEO of the now bankrupt FTX crypto exchange and Alameda Research, exposing the once-time world’s youngest billionaire as the Crypto-King with No Clothes… or maybe just in a rumpled t-shirt, cargo shorts and limp white socks.

Author Michael Lewis is a prolific and award-winning writer in the realm of business, finance, and economics—with an innate skill to find the human factor at the core. He was born in 1960 in the city of New Orleans, LA, to community activist Diana Monroe Lewis and corporate attorney, J. Thomas Lewis. He attended Isidore Newman, a co-ed nondenominational private school in New Orleans, then went on to Princeton University and graduated with a B.A. in art and archaeology in 1982. With no particular job prospects, Lewis enrolled in the London School of Economics, and received an MA in economics in 1985. With economics degree in hand, Saloman Brothers hired him as a bond salesman for their London office, infusing Lewis with a bounty of material for his itch for writing, both as a journalist for heavy-hitters such as The Economist and The Wall Street Journal, and as a prolific non-fiction author.

Lewis’s first book, inspired by his experiences in the mortgage-backed bond world, was Liar’s Poker (1989), followed by (abbreviated list): The New New Thing (1999), Moneyball (2003), The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game (2006), The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine (2010), Flash Boys (2014), The Fifth Risk (2018) and The Premonition: A Pandemic Story (2021). The Blind Side, Moneyball and The Big Short were all adapted into successful feature films.

Lewis has a storied career of exposing the idiocy and, at times, the insanity beneath the Fellini-like spectacles of the top 1% of society. But in October, 2023, Lewis dropped his book, Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon, based on the story of Sam Bankman-Fried, CEO of FTX until it all came tumbling down. In Going Infinite, Lewis describes Bankman-Fried as a brilliant man-child playing a high stakes game of ‘King of the Mountain’ atop a pile of crypto coins.

Cryptomania

There’s always the ‘new thing’ in the world’s financial systems, but the advent of unregulated cryptocurrencies adds a new level of volatility in our financial systems—sadly, we ever appear doomed to repeat history. As early as the 1600s, a hysteria blossomed in The Netherlands with a Dutch tulip market frenzy, affectionally dubbed, Tulipmania, in which fortunes were won and lost with the toss of a bulb. Seems bizarre, but with the array of crypto coins, it’s as if this new game is played with an ever changing ‘Tulip’, creating a multi-dimensional roller-coaster of mania.

From what I can discern, the major difference between the events leading up to ‘The Big Short’ and the Great Recession, versus the cryptocurrency meltdown, is that the crypto tycoons haven’t really cracked the US market and, at least as yet, haven’t fully seeped into the lobbyist system compared to the deep reach of Wall Street. However, the silver-lining of the FTX trial and conviction may be setting a legal precedence before the crypto lobbyists get a foothold into Congress.

Going Infinite

Lewis’s book begins by excavating Bankman-Fried’s childhood of isolation and game playing; a kid raised by professorial parents, perhaps in an atmosphere where reality and accountability were less valued than gaming… or the rule of law. As the story progresses, Lewis paints a portrait of Sam Bankman-Fried as, in some form or fashion, a savant man-child on a spectrum, who then surrounds himself with a motley crew of tech geeks—none of whom seem to truly understand the nuts and bolts of running a billion-dollar enterprise. However, these courtiers, after the money disappears, ultimately turn on Bankman-Fried, celebrating his demise like the kiddoes in William Golding’s novel, Lord of the Flies. Though under appeal at the time of this writing, the jury in the New York court case found Bankman-Fried guilty on all counts—but whether he purposely defrauded his investors through FTX and Alameda Research or that the business was grossly mis-managed is almost beside the point—the money is still in the ether. Or in someone’s offshore account.

So, at the end of the day, what is Sam Bankman-Fried’s true personality—is he a misunderstood genius, clueless as to corporate governance—or is he a sociopath and conman? Two things can be true at once. As Lewis unveils his deep-dive into Bankman-Fried, he portrays an intriguing young man running a multi-billion-dollar crypto business like a complex game, making up the rules as he went along. Christina Rolle, the Bahamas chief financial regulator, instrumental in effecting the country’s ‘open for business’ crypto stance, was quoted in Lewis’s book, as the end of FTX was near:

“It’s not hard to see you are being played by him [SBF], like a boardgame.”

It appeared that everything and everyone in Sam’s life was simply a game to be played.

Was the world simply distracted by the metronome of Bankman-Fried’s bouncing knee, seeing the ‘cool’ image rather than the man? In the financial world, due diligence is a basic requirement to analyze the veracity of company assets—and yet, if the assets are in crypto, evaluating worth can be as deceptive as a game of three-card monte. But, hey, that’s how the crypto cookie crumbles…

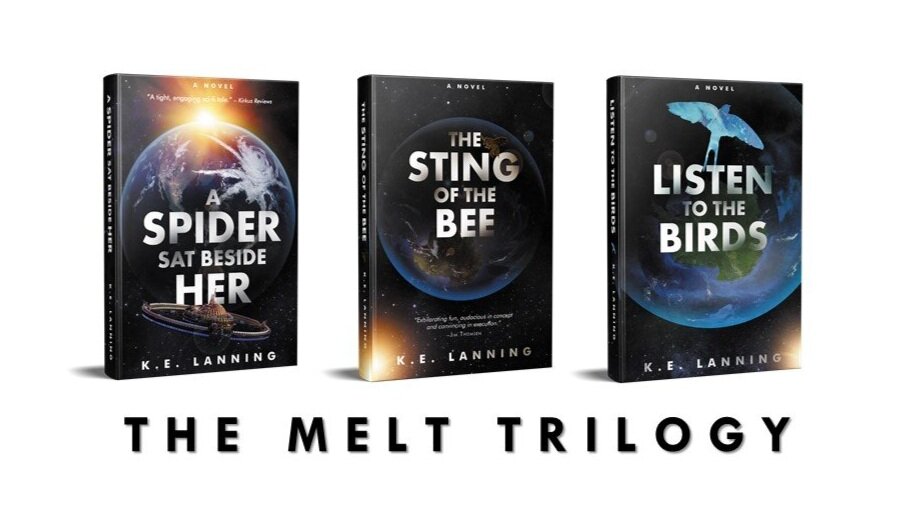

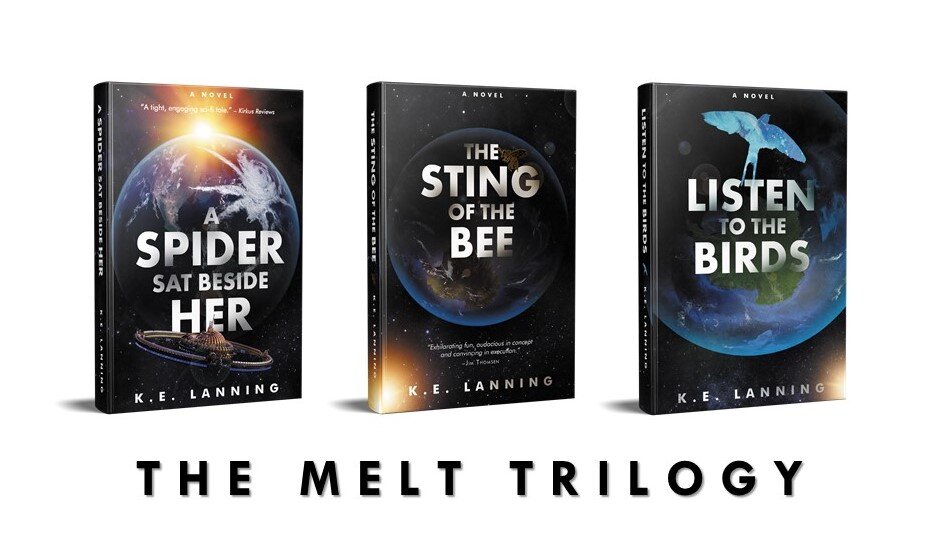

K.E. LANNING is an author and award-winning screenwriter, including a climate-fiction trilogy titled, The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds. She has two works of commercial literary fiction in progress: Where the Sky Meets the Earth and The Light of the Sun. In addition, she’s published a series of book reviews and author interviews, including authors Emily St. John Mandel, Kazuo Ishiguro, Hugh Howey, Margaret Atwood, Andy Weir, Claire Vaye Watkins, and Cixin Liu.

A SPIDER SAT BESIDE HER

So honored that the pilot script of A Spider Sat Beside Her advanced to the Second Round of the Austin Film Festival!! Woohoo! This puts the screenplay into the top 20% of the festival.

All aboard?

Well, kids, a few bits and pieces to tell you about… With encourage and feedback from two award-winning screenwriters, Brian Weakland and Terry Gau, I wrote the TV Pilot for A Spider Sat Beside Her as a part of a limited series (THE MELT). Script in hand, I was then invited to join a screenwriters’ group of over 30 years, which has spawned talents such as Vince Gilligan of BREAKING BAD and BETTER CALL SAUL. Needless to say, I’m delighted to be a part of the Virginia Screenwriter’s Forum.

With a leap of faith, I entered the pilot screenplay into a slew of screenwriting contests. A few days ago, I was notified that the script for A Spider Sat Beside Her had won the Best TV Pilot Screenplay Award for Drama from the New York Screenwriting Awards … Wow! Cross fingers that I’m on track with this puppy, and a few more contests fall my way!

Now to get back to my current novel in progress…

Well... it's finally begun.

With encouragement from a mentor (or two) on the Virginia Screenwriters Forum, I’ve taken the plunge and am writing a screenplay adapted from my book, A Spider Sat Beside Her. I plan to present a ‘pilot’ episode early next year to the forum, and then begin submitting to screenwriting competitions. Ideally, this first story in The Melt Trilogy would kick off a potential limited series based on the three novels. Cross-fingers for me—chances are slim-to-none that it will go anywhere, but what the heck—it’s worth a shot!

I hope 2023 brings good health and Zen to us all.

K.E. Lanning

Lost in the Time of Covid

COVID finally caught me in the spring of 2022. The virus gripped me in a malaise of fatigue and pain—and despair. Surging blood pressure, coughing until my chest ached, exhaustion and brain fog—all demanding that I rest, rest, rest. Many nights, as I lay in bed, I would imagine and then reimagine scenes in my half-completed manuscript. But, as I tossed and turned, I wondered—would I live to finish this novel? Or would I die, leaving my words stranded? Days merged into weeks . . . and then months.

Sick and weak, I lay in my room, gazing at the changing nature outside my window. In April, the winds rolled like waves, the moan of each gust rising as it approached, bowing branches with tender leaves, showering pollen in its wake. In May, the leaves stretched to full length, trembling in passing breezes. In June, emerald leaves hung listless until puffy clouds gathered, then darkened and raced across the sky, heralding their arrival with bursts of lightning and growls of thunder, pummeling the earth with rain.

Somehow, it seemed appropriate that I read Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time.

In Search of Lost Time

Written in the first person, Marcel Proust’s prodigious multi-volume novel is regarded as a loose version of his own life. The story begins with the narrator as a young boy, retiring early to his bed, listening to parties outside his room, and desperately missing his mother’s presence.

As the story unfolds, the narrator describes life in the fictional town of Combray believed to be modeled after the real village of Proust’s own childhood, Illiers, renamed in 1971 to Illiers-Combray in his honor. With lyric prose, he takes us with his family along walks through the village and countryside.

“…we would be met on our way by the scent of his lilac-trees, come out to welcome strangers. Out of the fresh little green hearts of their foliage the lilacs raised inquisitively over the fence of the park their plumes of white or purple blossom, which glowed, even in the shade, with the sunlight in which they had been bathed.”

Proust wrote visually. The reader yields to his immersive, detailed images, seen from the narrator’s eyes, of the beauty of the landscape, his daily encounters with family and friends, and the varied rooms in which he lives. And his tangled relationship with life itself.

But overshadowing the narrator, from childhood through his final days, is a debilitating asthma—each breath precious and illusive. The same disease which plagued Proust himself. He spent his last years confined to his bedroom, sleeping during the day and working at night on his novel. In 1922, one hundred years ago, Marcel Proust died of pneumonia at the age of fifty-one.

The Light at the End

An excerpt from Volume II, Within a Budding Grove, resonated with my state of mind as I finally imaged the light at the end of COVID:

“Once again I had escaped from the impossibility of sleeping, from the deluge, the shipwreck of my nervous storms. I feared now not at all the menaces that had loomed over me the evening before, when I was dismantled of repose. A new life was opening before me; without making a single movement, for I was still shattered, although quite alert and well, I savored my weariness with a light heart; it had isolated and broken asunder the bones of my legs and arms, which I could feel assembled before me, ready to cleave together, and which I was to raise to life merely by singing, like the builder in the fable.”

As the grass withers in the summer of 2022, I have returned to writing my novel, fed, in part, by hazy revisions in those midnight hours.

Karen (K.E.) Lanning www.kelanning.com , author of the cli-fi series, The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds, and currently writing two commercial literary novels: Where the Sky Meets the Earth and The Light of the Sun.

Review on Emily St. John Mandel's 'Sea of Tranquility'

Canadian author Emily St. John Mandel’s sixth novel, Sea of Tranquility, is graced with an idyllic title, but her apocalyptic work is far from peaceful. Her complex characters grapple with rumors of plague—and the reality of it—along with the aloneness of being human in derelict worlds of past and present.

Mandel, born in 1979 in Comox, British Columbia, Canada, was raised on the scenic Denman Island off of Vancouver Island. In this crucible of nature, she was homeschooled until fifteen years old, and then left high school at the age of eighteen to attend the School of Toronto Dance Theatre. Mandel currently lives in New York City with her husband and daughter.

In 2009, Mandel published her first novel, Last Night in Montreal, and then in 2010, released The Singer’s Gun, followed by The Lola Quartet in 2012. Mandel’s breakout moment came when her fourth novel, Station Eleven (published in 2014), won the 2015 Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Toronto Book Award. In addition, Station Eleven was shortlisted for the National Book Award and nominated for both the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction and the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction. The novel has been translated into 31 languages—and put Mandel firmly on the international literary scene.

Loosely based on Bernie Madoff’s infamous Ponzi scheme, Mandel published The Glass Hotel in 2020, in which her character, Jonathon Alkaitis, takes the reader along a tale of infamy, where deceit rips through the innocent and the gullible, their lives destroyed by insatiable greed. A line from the novel, “Money is its own country,” underlines the credence and allowance of our society to grant the rich—the aristocracy of the new world order—their own laws independent of those beneath them. And then the phrase, “Why don’t you swallow broken glass,” is mysteriously etched on a windowpane of the isolated Hotel Caiette, owned by Alkaitis, illustrating the paradox of having it all and yet having nothing. The novel was shortlisted for the Giller Prize and in 2019, NBC Universal International Studios acquired the rights to turn the story into a TV series.

In her upcoming novel, Sea of Tranquility, Mandel strums our instinctual human anxieties, interweaving disparate stories on warped and tangled strands of time. The character Edward muses in his exile to British Columbia, that, “This place is utterly neutral on the question of whether he lives or dies … it doesn’t care about his last name or where he went to school,” underlining that Nature is indifferent to us—we either eat or are eaten—a zero-sum game to the universe. In the timeline of one character, author Olive Llewellyn, a pandemic hits, crashing onto lives who’ve denied their vulnerability or refused to believe the apocalypse had finally arrived—until the final capitulation of acknowledgement, “We knew it was coming.”

Mandel’s flawed characters are expertly choreographed through centuries of time and space, human beings who are simply trying to live their lives in a complex and chaotic world. Perhaps her character, Gaspery, in Sea of Tranquility says it best, describing life on the edge: “A whiff of disorder that I found invigorating.”

Karen (K.E.) Lanning www.kelanning.com , author of the cli-fi series, The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds, and currently writing two commercial literary novels: Where the Sky Meets the Earth and The Light of the Sun.

Author K.E. Lanning, photo credit V Paulk

Dissent

Yesterday, I ran across a copy of Henry David Thoreau’s famous essay, On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. As I reread his essay, originally published in 1849, his words once again resonated in this era of peaceful marches against police brutality committed upon our fellow citizens.

In Thoreau’s time, the stakes were even higher—an abolitionist, he advocated withdrawing support of the government and in his case, stop paying taxes, to protest slavery and the Mexican-American war waged by an expansionist United States.

“Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison.... where the State places those who are not with her, but against her,—the only house in a slave State in which a free man can abide with honor.... Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence. A minority is powerless while it conforms to the majority; it is not even a minority then; but it is irresistible when it clogs by its whole weight. If the alternative is to keep all just men in prison, or give up war and slavery, the State will not hesitate which to choose. If a thousand men were not to pay their tax bills this year, that would not be a violent and bloody measure, as it would be to pay them, and enable the State to commit violence and shed innocent blood. This is, in fact, the definition of a peaceable revolution, if any such is possible. [...] But even suppose blood should flow. Is there not a sort of blood shed when the conscience is wounded? Through this wound a man's real manhood and immortality flow out, and he bleeds to an everlasting death. I see this blood flowing now.”

In an eloquent excerpt, Thoreau writes:

“If the injustice is part of the necessary friction of the machine of government, let it go, let it go: perchance it will wear smooth—certainly the machine will wear out. If the injustice has a spring, or a pulley, or a rope, or a crank, exclusively for itself, then perhaps you may consider whether the remedy will not be worse than the evil; but if it is of such a nature that it requires you to be the agent of injustice to another, then I say, break the law. Let your life be a counter friction to stop the machine. What I have to do is to see, at any rate, that I do not lend myself to the wrong which I condemn.”

From On the Duty of Civil Disobedience, H.D. Thoreau, 1849

Mahatma Gandhi, impressed by Thoreau’s arguments, wrote in 1907,

“Thoreau was a great writer, philosopher, poet, and withal a most practical man, that is, he taught nothing he was not prepared to practice in himself. He was one of the greatest and most moral men America has produced. At the time of the abolition of slavery movement, he wrote his famous essay On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. He went to gaol for the sake of his principles and suffering humanity. His essay has, therefore, been sanctified by suffering. Moreover, it is written for all time. Its incisive logic is unanswerable.”

— "For Passive Resisters" (1907)

In his quest for liberty from Britain, Gandhi adopted peaceful civil disobedience and ultimately won independence in 1947. “Civil disobedience becomes a sacred duty when the state becomes lawless and corrupt.”

Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote in his autobiography:

“During my student days I read Henry David Thoreau's essay On Civil Disobedience for the first time. Here, in this courageous New Englander's refusal to pay his taxes and his choice of jail rather than support a war that would spread slavery's territory into Mexico, I made my first contact with the theory of nonviolent resistance. Fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system, I was so deeply moved that I reread the work several times.

I became convinced that noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. No other person has been more eloquent and passionate in getting this idea across than Henry David Thoreau. As a result of his writings and personal witness, we are the heirs of a legacy of creative protest. The teachings of Thoreau came alive in our civil rights movement; indeed, they are more alive than ever before. Whether expressed in a sit-in at lunch counters, a freedom ride into Mississippi, a peaceful protest in Albany, Georgia, a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, these are outgrowths of Thoreau's insistence that evil must be resisted and that no moral man can patiently adjust to injustice.”

— The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.

King made nonviolent protests a key component to his civil rights activism. “Mass civil disobedience can use rage as a constructive and creative force.”

On this New Year’s Eve of 2021, I remember the crowds of people over these last years, in the midst of a pandemic, peacefully assembling in towns and cities across the world for those who have wrongly died in the hands of law enforcement. For eight minutes and 46 seconds we knelt for George Floyd, with the words, “I can’t breath,” pounding in our minds and hearts. For, as citizens, we must demand justice—it is not only our right, but our duty.

K.E. Lanning

Review of Claire Vaye Watkins's novel, 'I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness'

I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness is Claire Vaye Watkins’s latest novel, [released October 5th, 2021] and is written in the form of a memoir interlaced with her family saga—one can imagine a tattered journal, interwoven with detritus from past and present, pages scrawled in a corner of the Vegas airport or under the branches of a Joshua tree, its cover cracked from the heat of the desert—stories of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll and vagina dentata—what more could you want?

Bio

Born in Bishop, California in 1984, Watkins grew up in the Mojave Desert on the fringe of Death Valley—first in Tecopa, California and then Pahrump, Nevada, living in a desert landscape of sand and gravel, yucca and mesquite, edged by the gray chiseled Nopah Range—the extremes of life and death of nature in striking distance of the fantasyland of Vegas. But Watkins’s unique upbringing was not only the desert—her father was Paul Watkins, a member of the Charles Manson Family. By illuminating Manson’s “Helter Skelter” motive, he ultimately brought Manson to justice after the horrific Tate and LaBianca murders in Los Angeles. Watkins describes her mother, Martha, as “a great bullshitter” and “incredible dynamo” who found a way to survive in a grueling world. Her parents met at the Crowbar bar on the edge of Death Valley, married, and had two daughters, Claire and Lise Watkins.

Watkins received her Bachelor’s degree from the University of Nevada, Reno and her Master of Fine Arts from Ohio State University. She has taught at Princeton and Bucknell universities, and was an assistant professor at the Helen Zell Writers’ Program at the University of Michigan. Currently, Claire Vaye Watkins teaches creative writing at the University of California, Irvine.

Literary Debut

Watkins made her literary debut in 2012 with a collection of short stories, Battleborn, earning literary accolades on multiple fronts. The New York Times called the collection, “brutally unsentimental,” and The New Yorker wrote that Watkins is writing in an entirely new genre: “Nevada Gothic.” Battleborn won The Story Prize, The Dylan Thomas Prize, the New York Public Library Young Lions Fiction Award, The Rosenthal Family Foundation Award and The Silver Pen Award from the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame. She has been published in a slew of respected publications: Granta, Tin House, Freeman’s, The Paris Review, Story Quarterly, New American Stories, Best of the West, The New Republic, The New York Times, and Pushcart Prize XLIII, to name a few. Watkins was included in the National Book Foundation’s “5 under 35,” Granta’s “Best Young American Novelists,” and awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Her first novel, Gold Fame Citrus, published in 2015 by Riverhead, is a work of stunning speculative fiction, and hit the literary scene with a flurry of critical praise, named the Best Book of the Year by a host of publications: The Washington Post, NPR, Vanity Fair, LA Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Huffington Post, The Atlantic, Refinery 29, Men's Journal, Ploughshares, Lit Hub, Book Riot, Los Angeles Magazine, Powells, BookPage, and Kirkus Reviews.

The near future story is set on a West Coast suffering extreme drought with shifting sand dunes driving out all but the dregs of society, who, like rats, rifle through the scraps of the rich and famous who have fled the Golden State. As the main characters flee eastward from California, they discover a tribe in the desert—a commune of the insane, the desperate, and the unlucky—led by an enigmatic master.

Watkins’s dystopian parable weaves metaphor and angst as desperate and tenuous humans cling to life within oceans of sand. With vestiges of Orwell and LeGuin, she scatters her disturbing “Alice in Wonderland” existence with peculiar and broken characters, irrevocably wounded by life.

I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness

If Gold Fame Citrus can be described as intensely surreal, then Watkins’s latest novel, I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness, is a foil in a way—the brutal realism of life. Primarily told in the first person, the story has a disjunctive feel: Claire’s anguished memoir, jumbled with stories from her father’s past, and, in reverse chronological order, her mother’s old letters to her cousin Denise, inserted at random places, as if tucked within the pages of a book.

The novel begins after the birth of the main character’s first child, and Claire sinks into a quicksand of post-partum depression, and attempts to persuade herself that this will pass.

“I would be okay—would survive my child’s first winter, a sludgy era of despair, bewilderment, and rage passed in the palm of the mitten.”

As Claire tries to come to terms with her life, she recalls the stark grief of losing Jesse, a lover from her past, in a wreck:

“There is a shattered windshield, a cop car, an ambulance, a fire engine tilted on the soft shoulder of the highway, lights blazing. The sun is rising and the mountains are indigo above you. Someone has tucked you up so none of you is showing so we don’t have to see the parts of you we don’t want to.

You were here, then you were gone.”

Watkins peppers a wry and, at times, bitter humor within her narrative, and yet the novel’s essential humanity is poignantly revealed in Claire’s attempt to understand the dysfunctional love of her family:

“We have loved and loved and been loved despite the fissures and loses, violence, cruelty, smallness, timing, deficits in money and time and attention, despite the betrayals and indifferences, the distance and weather, despite developing different definitions of certain words. Death, expensive, cold.”

There is a deep, stark honesty in I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness—where one finds comfort in the shadows—hiding from the vulnerability and powerlessness of love. Though life can be beautiful, it’s also a journey through a valley of heartache, sorrow, and loss—and at its deepest abyss—a place where fear trumps love. As the old expression goes, perception is everything, but in our flawed myopic vision, is what we think we see real, or is the world simply a chaotic and surreal mirage? I guess it depends on how good the drugs are…

Please check out my fantastic interview with Claire Vaye Watkins on The Millions.

Additional links to I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/668168/i-love-you-but-ive-chosen-darkness-by-claire-vaye-watkins/

https://bookshop.org/books/i-love-you-but-i-ve-chosen-darkness/9780593330210

Karen (K.E.) Lanning www.kelanning.com , author of the cli-fi series, The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds, and currently writing two commercial/literary novels: Where the Sky Meets the Earth and The Light of the Sun.

JD DeHart Interview with K.E. Lanning on Writing

JD DeHart is a poet, author, and reviewer—he kindly asked to interview me in 2018, but life got involved, I’m only now publishing it on my blog! This interview was just after I’d completed the first book in The Melt Trilogy, A Spider Sat Beside Her, and I was writing the second book, The Sting of the Bee. (JD DeHart’s Interview Questions in Bold)

What drives you to write?

All my life, I’ve been an explorer of ideas—like nuggets of gold, ideas are the jewels of the mind. A creative drive has always been within me; drawing, photography, and even directing an art gallery for several years, but my degree in physics honed my mind to be deductive in thought.

For me, writing is the culmination of all of my creative juices and the desire to dig into the human condition within the framework of a novel. A Spider Sat Beside Her is my debut novel, and the first book within a trilogy of novels on the relationship of humans to the Earth.

What would you like readers to know about your books?

I want readers to come to these novels with an open mind, but leave them with ideas to take away. World building is unique to science fiction and the first novel, A Spider Sat Beside Her, constructs my post-Melt world, and the story is set in motion by these global warming events.

In A Spider Sat Beside Her, with a global event like the catastrophic melting of the ice caps, I needed to convey prospective, so I wrote a series of vignettes, inspired by John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, where he utilized a narrator’s voice and disembodied voices within the novel to convey the broader context to the Joad family’s story of migration.

Once I build a world, I develop plot using both projections into the future and historical events, because history always repeats itself, given the same catalysts. The entire trilogy is also about what could be—Antarctica being a fresh canvas—I’ve created a world where humans are in balance with nature . . . until some of them decide to take advantage of the fragile power structure.

Please describe your writing process.

I am a non-linear writer—I write in circles rather than in a straight line. I start with a concept and play with that for a while, to develop the big picture. Once I have the setting and initial idea of main characters, then the story begins to roll. In the novel I’m currently writing, The Sting of the Bee, the human urge to escape from a decrepit ‘Old World’ to a ‘New World’ is the seed of the story.

In nuts and bolts, I begin the story for several chapters, then jump to the end, and then return to the middle to complete the manuscript. It’s traditional building of a novel with skeleton, meat, and skin, but perhaps in a different sequence. I’ve found that figuring out the conclusion helps me determine the middle, and also aides with devices such as foreshadowing. I do multiple passes through the manuscript to expand thin spots and create smooth transitions. Many times I have epiphanies of what the novel is trying to say, and add accordingly.

What advice would you offer young writers?

Read the classics, fiction and non-fiction, including writers such as Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Mead, and Malcolm Gladwell. Understand human behavior, economics, science, and politics, to help you to create a novel that has depth and significance. You can have beautiful prose, but it must strike the reader’s heart and mind or, like the old saying, it’s dust in the wind.

Study the craft of writing and endeavor to make your word, your sentence, your paragraph, your chapter—your novel, the best it can be. Figure out your weaknesses and find people to augment those. Develop a very thick skin—it’s not about you—it’s about the writing. Be obsessive, but get it out there.

What are you reading and writing now?

I am currently reading The Year of the Flood, by Margaret Atwood; such a fantastic author!

As far as writing, I am completing the second book in my trilogy, The Sting of the Bee, which is scheduled to launch next year. Weirdly enough, this was the first story I wrote, but I wanted to publish A Spider Sat Beside Her prior to The Sting of the Bee, partially to develop the stage for the subsequent books. However, all of the books within the trilogy are standalone; I didn’t want to leave the reader with a cliffhanger, but have a satisfying ending to each book.

Where can we learn more about you and your books?

I have a website: www.kelanning.com and you can subscribe there to receive published blog articles and updates on my novels. I also have author pages on Goodreads and Amazon.

Thanks so much, JD, for the interview!

K.E. Lanning

Originally published on JD DeHart’s blog and check out JD DeHart's Amazon page

Amazon Links to THE MELT TRILOGY:

A Spider Sat Beside Her

The Sting of the Bee Listen to the Birds

Review of Kazuo Ishiguro's latest novel, "Klara and the Sun"

Author Kazuo Ishiguro, photo credit: Jeff Cottenden

Author Kazuo Ishiguro’s latest novel, Klara and The Sun, is a masterful parable on humanity—whether that humanity is flesh and blood or, in Ishiguro’s futuristic story, is found within Klara, an “Artificial Friend,” built of metal and integrated circuits. With Ishiguro’s elegant brushstrokes, the story unfolds gracefully, an intricate watercolor of translucent colors layered one upon another, until the image coalesces, revealing a tale of anguish and desperation.

But who is Kazuo Ishiguro? Born in Nagasaki, Japan on November 8, 1954, he’s the son of oceanographer, Shuzuo Ishiguro, and his wife, Shizuko. At the age of five, he and his family left Japan and moved to England, living in Guildford, Surrey. He is described as a British Asian author—raised to adulthood in England, but within a Japanese family—his feet firmly planted in each culture, allowing Ishiguro to have a perspective of life unique from his English contemporaries.

Ishiguro attended Stoughton Primary School and Woking County Grammar School in Surrey, then traveled extensively through the United States and Canada. In 1974, he attended the University of Kent at Canterbury, graduating in 1978 with a Bachelor of Arts in English and Philosophy. Afterward, he spent a year writing fiction, then studied at the University of East Anglia with Malcolm Bradbury and Angela Cartier, graduating in 1980 with a Master of Arts in Creative Writing. His thesis became his first novel, A Pale View of Hills, published in 1982. Ishiguro became a UK citizen in 1983 and was knighted in 2019 for his services to literature. Currently, Ishiguro lives in London with his wife, Lorna MacDougall and their daughter, Naomi Ishiguro, who is also pursuing a literary career.

A critically acclaimed author, Ishiguro received the Man Booker Prize in 1989 for his novel, The Remains of the Day, subsequently adapted in 1993 into a major motion-picture film of the same title, and nominated for eight Academy Awards. His 2005 novel, Never Let Me Go, was named by Time magazine as the best novel of the year. In 2017, Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize in Literature, with the Swedish Academy describing him as a writer "who, in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world." And, to show the depth of his writing talent, he’s co-written multiple songs with jazz singer, Stacey Kent, including lyrics on the 2007 Grammy-nominated album, Breakfast on the Morning Tram.

Ishiguro has published nine novels, utilizing whatever genre fits his needs for a particular story. The Remains of the Day is a historical period piece—a searing and brilliant character portrait of an English butler, and the novel, Never Let Me Go, explores the ethical dilemmas of organ donation in a parallel world during the 1980s and 90s. His literary fantasy novel, The Buried Giant [2015], is a stunning and heartbreaking tale of grief and loss. Ishiguro writes in unadorned prose, shorn of device and casual metaphor, and yet he creates powerful allegorical scenes within his stories.

Klara and the Sun, the first novel he’s published since winning the Nobel Prize for Literature, was released on March 2nd, 2021, and is set in a dystopian future where specially programmed robots are sold as human companions. The story is told from the point of view of Klara, an “Artificial Friend,” opening the story as a nascent robot, innocent and “happy,” and like an infant, she observes the world from the window of the AF store. Once she is purchased for a sick girl named Josie, Klara struggles to comprehend the angst-ridden humans surrounding her and their complex relationships. In a lovely excerpt, Klara fights her way through a field of tall grass to an old barn where she believes the Sun sleeps—a symbolic passage of her struggles to navigate her chaotic world.

Excerpt from Klara and the Sun:

“One moment the grass would be soft and yielding, the ground easy to tread; then I’d cross a boundary and everything would darken, the grass would resist my pushes, and there would be strange noises around me, making me fearful that I’d made a serious miscalculation . . .”

But is Klara and the Sun a mirror reflecting our human weaknesses, or a window on our looming quandaries, as we humans, naïve gods that we’ve become, create sentient beings without understanding how these entities will truly merge into human society.

K.E. Lanning, author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds.

This article is also available at the online magazine: FUTURISM

Ursula K. Le Guin's 'The Lathe of Heaven' on its Fiftieth Anniversary

Original Hardcover of Lathe of Heaven - 1971

Ursula K. Le Guin’s novels defy classification as to whether they are speculative fiction or simply literary fantasy—her exquisite prose creating rich tapestries, surreal dreams of plot and character, woven with fierce threads of social and philosophic commentary.

The Lathe of Heaven was published in 1971, following her blockbuster success with her 1969 novel, The Left Hand of Darkness, but Le Guin’s writing career began in the late 1950’s, strongly influenced by cultural anthropology, Taoism, feminism, and the writings of Carl Jung.

The title, The Lathe of Heaven, is taken from the writings of Chuang Tzu (Zhuang Zhou), a passage from Book XXIII, paragraph 7, quoted as an epigraph to Chapter 3 of the novel:

“To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven.”

Le Guin chose the title because she loved the quotation. However, it seems that the quote is a mistranslation of Chuang Tzu's Chinese text. In an interview with Bill Moyers recorded for the 2000 DVD release of the 1980 adaptation, Le Guin clarified the issue:

“...it's a terrible mistranslation apparently, I didn't know that at the time. There were no lathes in China at the time that that was said. Joseph Needham wrote me and said "It's a lovely translation, but it's wrong."

Regardless of the misinterpretation of the original text, the title stands as a singularly powerful concept.

The Lathe of Heaven

The story is set in Portland, Oregon, in 2002, in a world devastated by global warming, poverty due to overpopulation, and Middle East wars. The protagonist, George Orr, is a draftsman who abuses drugs in an attempt to stifle his ability to dream—he has discovered, to his abject terror, that when he dreams “effective” dreams, they alter reality; however, he is the only one who recalls the previous reality. Because of his illegal drug abuse, he is forced to undergo “voluntary” psychiatric care under a psychiatrist and sleep specialist named William Haber. Haber discovers that he can influence George’s dreams and becomes a type of puppet master over him, manipulating reality to “save the world”, but also enhance Haber’s wealth and status. Under Haber’s machine, the Augmentor, he uses George’s power to “do good” but he cannot control George’s dreams, and bizarre, twisted realities ensue. George realizes Haber’s dubious plan and enlists a lawyer, Heather Lelache, to represent him against Haber’s scheme, with limited success as reality continues to be altered, including her own existence.

The novel was initially serialized in the American science fiction magazine Amazing Stories. The novel received nominations for the 1971 Nebula Award, the 1972 Hugo, and won the Locus Award for Best Novel in 1972. The novel was adapted to film by PBS and released in 1980 with Le Guin involved in the production of the adaptation. A second adaptation was released in 2002; however discarding a significant portion of the story.

Ursula K. Le Guin

Born Ursula Kroeber in Berkeley, California, 1929, she grew up on the Pacific Coast, immersed in anthropologic worlds through her father, tales handed down through her family, and classic literature. Le Guin graduated from Radcliffe in 1951, married historian Charles Le Guin in 1953 and they had three children, Elisabeth, Caroline, and Theodore. In 1959, the family settled in Portland as their permanent residence.

During an interview with Mark Wilson, Le Guin discusses her early influences: “Once I learned to read, I read everything. I read all the famous fantasies – Alice in Wonderland, and Wind in the Willows, and Kipling. I adored Kipling's Jungle Book. And then when I got older I found Lord Dunsany. He opened up a whole new world – the world of pure fantasy. And ... Worm Ouroboros. Again, pure fantasy. Very, very fattening. And then my brother and I blundered into science fiction when I was 11 or 12. Early Asimov, things like that. But that didn't have too much effect on me. It wasn't until I came back to science fiction and discovered Sturgeon – but particularly Cordwainer Smith. ...I read the story Alpha Ralpha Boulevard, and it just made me go, "Wow! This stuff is so beautiful, and so strange, and I want to do something like that."

In the 1960s, Le Guin found her voice through science fiction, publishing her first novel, A Wizard of Earthsea in 1966. By 1970, she had won the Hugo and Nebula awards for The Left Hand of Darkness [1969] an exquisite novel exploring gender and the concept of “otherness”. In the year following, Robert Heinlein published his novel, I Will Fear No Evil [1970] exploring male and female sexuality, but he never crossed the boundary into the deconstruction of gender like Le Guin's brilliant concept in The Left Hand of Darkness—the idea that gender is not absolute, but ephemeral. Jo Walton at Tor Books wrote a lovely article on The Left Hand of Darkness and Le Guin: Gender and glacier: Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness

With multiple awards in her literary career, Le Guin is considered one of the greatest speculative fiction writers of all time. Over her career, she received numerous accolades, including eight Hugos, six Nebulas, and twenty-two Locus Awards, and in 2003 became the second woman honored as a Grand Master of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. In 2000, the U.S. Library of Congress named her a Living Legend, and she won the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 2014. Le Guin has influenced many other authors, including Booker Prize winner Salman Rushdie, David Mitchell, Neil Gaiman, and Iain Banks. After her death in 2018, critic John Clute wrote that Le Guin had "presided over American science fiction for nearly half a century", and author Michael Chabon referred to her as the "greatest American writer of her generation".

Ursula K. Le Guin, photo credit Jack Liu

In 2016, Julie Phillips wrote a superb article on Le Guin for the New Yorker: The Fantastic Ursula K. Le Guin, including an intimate conversation with Le Guin at her Portland home.

Le Guin died on January 22, 2018 at the age of 88, but her literary heritage will continue to influence, be it bur or spur, on our society. I leave you with a prescient quote from Ursula K. Le Guin in 2014:

“I think hard times are coming when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies. We will need writers who can remember freedom. Poets, visionaries – the realists of a larger reality.”

—Ursula K. Le Guin

Many thanks to Wikipedia for background of Ursula K. Le Guin and to interviewers: Mark Wilson, Jo Walton of TOR, and writer Julie Phillips, contributor to The New Yorker.

K.E. Lanning, author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds; and her upcoming novel: Where the Sky Meets the Earth.

This article was also published on FUTURISM on January 7, 2021.

A Ruthless World?

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, photo courtesy of Lynn Gilbert

Speculative fiction asks the question, “What if?” But in the real world, what if Ruth Bader Ginsburg had not existed? Would the dystopia of Margaret Atwood’s Hand Maid’s Tale be knocking at our door? It’s hard to know the butterfly effect of such a scenario on our modern society, but we do know, and have lately seen, how the dark forces of authoritarian dominance can destroy our civil liberties. Bold in her approach and tenacious in truth, Ruth stands with the giants in the crusade for freedom of the individual, not just freedom for women, but for every human being, because civil rights for one, spreads to all.

The Renaissance is viewed as a time for great art and science, but the true paradigm shift was a spark of consciousness—the individual is significant and each human being has worth and weight in this world. From the early Greek experiment to the radical idea that human beings have universal natural rights to liberty and essence, we’ve carved our democratic principles and rules of law. The individual right to vote—no matter the color of your skin or your gender—took centuries of blood, sweat, and tears.

But it took a woman, small in stature and quiet of voice, to take on the Supreme Court of the United States to achieve equality for a human being who is, simply by chance, a woman.

K.E. Lanning

Author of The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

British host Andrew Eborn interviews me on Octopus TV - check it out!

British host Andrew Eborn interviews me for Octopus TV!! Fun time!

Animal Farm – 75th Anniversary and chillingly relevant

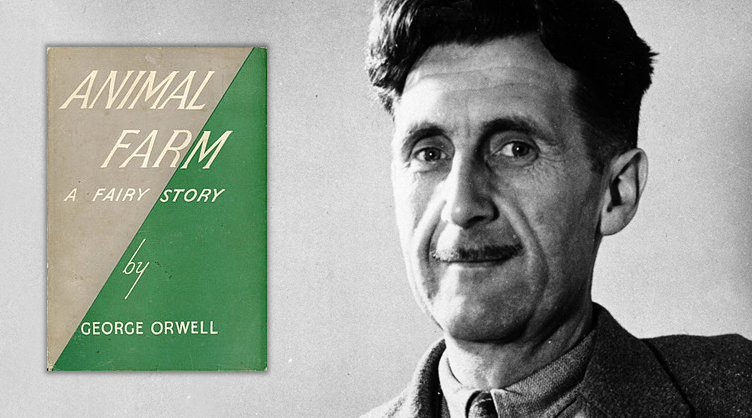

First edition cover (1945) for Animal Farm and author George Orwell

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others. Animal Farm, 1945

In the preface of the allegorical novella, Animal Farm, Orwell described the source of the idea of setting the book on a farm:

“...I saw a little boy, perhaps ten years old, driving a huge carthorse along a narrow path, whipping it whenever it tried to turn. It struck me that if only such animals became aware of their strength, we should have no power over them, and that men exploit animals in much the same way as the rich exploit the proletariat.”

Orwell began writing Animal Farm in March of 1943 and completed it in April 1944. Several publishers refused it, considering it an attack on the Soviet regime and, despite Stalin’s murderous purges, Russia was a crucial ally during WWII. Finally published on August 17th, 1945, Animal Farm resonated in the post-war era, achieving worldwide success, and Orwell became a celebrated figure.

Orwell described Animal Farm as a “fairy story” or fable reflecting the Russian Revolution and Stalinist era of the Soviet Union. The book weaves a story of farm animals who, led by two pigs, Snowball and Napoleon, rebel against their human farmer and attempt to create their own free and equal society. Power mad, Napoleon overthrows Snowball and the utopian society devolves into a dictatorship, with Napoleon now indistinguishable from the human owner the animals had ousted. Animal Farm was the first book in which Orwell tried, “to fuse political and artistic purpose into one whole.”

ORWELL’S EARLY LIFE

George Orwell was born Eric Arthur Blair on June 25th, 1903 in Motihari, India. He grudgingly attended Eton, and though not a stellar student, he was known as a practical joker and a young man who argued for argument sake. In 1922, he sailed to Burma and worked as a police officer until he contracted dengue fever in 1927, after which he returned to England. At this point, among a variety of occupations, he began his writing career, but Orwell’s tenuous health would continue to plague him for the rest of his life. Inspired by the River Orwell in Suffolk, England, he took on the pen name George Orwell in 1933 for the publication of his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London.

In 1936, Orwell went to fight against Fascism in the Spanish Civil War, but over time, he became disillusioned with the Communists, and after he and his wife escaped from Spain, he considered himself forced into the role of pamphleteer. “The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.”

ORWELL THE WRITER

Contemporaries of Orwell paint the picture of a man who struggled to become a writer through long periods of poverty, failure, and humiliation, but he turned the sweat and agony into literature [paraphrased from Fyvel]. Ben Wattenberg stated: "Orwell's writing pierced intellectual hypocrisy wherever he found it." According to historian Piers Brendon, “‘Orwell was the saint of common decency who would in earlier days,’ said his BBC boss Rushbrook Williams, 'have been either canonised—or burnt at the stake'"

In 1940, Orwell wrote: "The writers I care about most and never grow tired of are: Shakespeare, Swift, Fielding, Dickens, Charles Reade, Flaubert and, among modern writers, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot and D. H. Lawrence. But I believe the modern writer who has influenced me most is W. Somerset Maugham, whom I admire immensely for his power of telling a story straightforwardly and without frills." Elsewhere, Orwell strongly praised the works of Jack London, especially his book, The Road.

He wrote an essay in 1946, “Why I Write,” in which he details his journey to writing. He professes four motives for writing:

1. Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful business men – in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they abandon individual ambition – in many cases, indeed, they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all – and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.

2. Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.

3. Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.

4. Political purpose. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people’s idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

And yet Orwell famously said, “Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness.”

First Edition cover (1949)

In 1949, George Orwell went on to publish his best-known work, Nineteen Eighty-Four, a dystopian novel of government repression and overreach. He created a terrifying world in which the citizenry is trapped in a constant state of fear of unending wars versus “others” and controlled by surveillance and propaganda. The unnerving echo of political manipulation of the truth tolls like a bell across our world.

Orwell died from tuberculosis in 1950 at the age of forty-six, but his profound tales of totalitarianism are still relevant in their searing exposure of today’s societal ills.

IN THE YEAR 2020

On the seventy-fifth anniversary of Animal Farm, we’ve made progress on civil rights, women’s rights, and LGBTQ rights—and yet the rich and powerful are still “more equal” than others. How can this be? Where is the line between political satire and reality in our new millennium?

Inequality suits the powerbrokers, and so the deep-seated irrational fears of race, misogyny, sexual orientation and xenophobia are exploited by clever puppet masters in order to maintain control. And why Margaret Atwood’s chilling novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, has struck a deep chord within our not-so-perfect union in America and the world.

The sad truth of human nature is that bigotry is a cudgel of dominance—Orwell’s Animal Farm endlessly played out in real life, enabling a machine of intolerance—an institutional hierarchy. For those who doubt this system of privilege and power exists, just look into the eyes of Derek Chauvin as he coldly executes George Floyd—he knew was protected by this supremacy. Orwell’s words haunt us to this day: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

August 17th, 2020

K.E. Lanning, author of The Melt Trilogy

My in-depth interview with Margaret Atwood (audio version at top).

Many thanks to Wikipedia and The Orwell Foundation for background on George Orwell.

This article was also published on FUTURISM.

Perdido Street Station—the 20th anniversary of China Miéville’s critically acclaimed novel.

Where Fiction gets Weird

Author China Miéville, photo courtesy of Mic Cheetham Agency

Celebrating its twentieth anniversary, China Miéville’s award winning Weird/urban fantasy novel, Perdido Street Station (2000, Macmillan), is the opening salvo of his fictional world of Bas-Lag, a strange slurry of magic, steampunk, and post-modern enigmas. The second novel in the trilogy, The Scar, was published in 2002, and the final book, Iron Council (2004), completes the New Crobuzon trilogy.

China Miéville has received multiple awards for his works: the Arthur C. Clarke Award (three times), the World Fantasy Award, the British Fantasy Award (twice), the Hugo Award, the Locus Award (four times), the Kitschies, the BSFA Award and multiple nominations for various literary awards, including the prestigious Nebula Awards. His most notable works are: Perdido Street Station, The City & The City (2009), and Embassytown (2011), winner of the Locus Award for Best Science Fiction Novel in 2012. The City & The City, particularly relevant to our current political and social chaos, was adapted for a BBC television series in 2018:

Miéville sites multiple authors as influences in his writing, most notably, M. John Harrison, Mervyn Peake, Michael de Larrabeiti, and Ursula K. Le Guin. Miéville’s debut novel was King Rat (1998), an urban fantasy novel set in London during the end of the twentieth century, and nominated for both the Bram Stoker Award and the International Horror Guild Award in their First Novel category. Within the spectrum of fantasy writings, Miéville is firmly on the urban surrealism end as opposed to the Tolkien end of the genre. He is a prolific writer, not afraid to cross genres, and terms his novels simply as “Weird Fiction.”

So who is the illusive China Miéville? Besides being a fantasy fiction writer, he’s political activist, and an academic. Miéville was born in Norwich, England in 1972 and spent most of his early years in northwest London. His first name, China, springs from his parents’ desire for a beautiful first name, perusing a dictionary until they found the word China. His father left after his birth and he was raised by his American mother, Claudia, a writer, translator, and teacher. He credits playing Dungeons & Dragons as a youth for influencing the fantastical premise of his novels.

Miéville attended Oakham School in Rutland, England, and after graduation, taught English in Egypt for a year, developing an interest in Middle Eastern culture and politics. He received an undergraduate degree in social anthropology at Clare College in 1994, then a masters and PhD in international relations from the London School of Economics in 2001. During his graduate studies, he became disillusioned with materialistic aspects of capitalism and became a Marxist. His political bones become subtle threads within his novels, highlighting the abuse of power, bigotry, and the stratification of economic classes within society.

Perdido Street Station launched Miéville onto the sci-fi fantasy stage with creatures so detailed in their descriptions that you can almost feel the drool on the page. Miéville pings the end of the spectrum of ‘exotic’ in his sculpting of creatures, adding a dimension with his Remades, a cast of surgically altered beings. Beneath the rustle of feathers and the skin prickling insect-humanoids, are there metaphorical intentions of his creatures? Though Miéville distances himself from overt political content, eddies of social commentary lie beneath the surface. Miéville explores the human condition as his main character, Isaac, faces racism in his relationship with Lin, an exo-skeletal humanoid, while veins of corruption ooze through the city of New Crobuzon. In Perdido Street Station, the Construct Council, a sentient machine comprising myriads of small appliances (a corporate entity?), manipulates subtle control within the city, but ultimately helps in the fight against a monstrous species of deadly slakemoths.

The enduring success of Miéville’s works underscores a deep hunger for Weird fiction, a genre rooted in the works of Edgar Allan Poe. In the angst of the 1990s, Weird fiction met urban fantasy, and in 2002, in the introduction to China Miéville's novella, The Tain, M. John Harrison is credited with creating the term "New Weird." Rose O'Keefe of Eraserhead Press claims that "People buy New Weird because they want cutting edge speculative fiction with a literary slant.” Authors Jeff and Ann VanderMeer define the New Weird genre in their introduction to the anthology, The New Weird, as "a type of urban, secondary-world fiction that subverts the romanticized ideas about place found in traditional fantasy, largely by choosing realistic, complex real-world models as the jumping-off point for creation of settings that may combine elements of both science fiction and fantasy."

Miéville takes Weird fiction to its illogical and glorious end, taking our breaths away with his incredible worlds of urban fantasy. Perdido Street Station released twenty years ago? It seems like yesterday…

Author of: The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

Author K.E. Lanning Interview on PBS for The Melt Trilogy

Sharing a novel with readers is one of the best parts of being an author! I was privileged to be asked by my local PBS station to do an interview for The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds. So gentle readers, without further ado, here’s the interview which first aired on 1/14/2020:

I hope you enjoy it, and please forward as you will! Link url: https://www.pbs.org/video/write-around-the-corner-k-e-lanning-x8easy/

Now I have to get back to finishing my next novel, Where the Sky Meets the Earth - my editor awaits!

Best wishes for 2020 and welcome to a new decade!

K.E. Lanning

Review of Author Margaret Atwood's "The Testaments"

Author Margaret Atwood (photo credit: Liam Sharp)

Master Puppeteer of Dystopian Theater

“Praise be!” It has been thirty-four years since the controversial, and even banned novel, The Handmaid’s Tale was published (1985), and on September 10, 2019, Margaret Atwood published its sequel, The Testaments. Her latest novel has already garnered critical praise and was named to the shortlist for the Booker Prize.

In The Testaments, her characters bear witness to the inevitable corruption of power in the totalitarian regime of Gilead. Extreme societies tend to end extremely, and as phrased succinctly by Gilead's Aunt Lydia: “In time like ours, there are only two directions: up or plummet.”

The Handmaid’s Tale introduced us to the country of Gilead—a nation based on strict theocracy, and though the interlude has been long, the final act of the play is The Testaments, in which we observe the increasingly corrupt machinations of a state, or perhaps a twisted royal court, which hasn’t as yet recognized its internal wounds, bleeding away the strength of its original “truths.”

Margaret Atwood, born in Ottawa, Canada in 1939, knew by the age of sixteen that writing would be her profession. Atwood graduated in 1961 with a Bachelor’s degree in English from Victoria College in the University of Toronto, and in 1962, received a Master’s Degree from Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA. In 1961, she won the E.J. Pratt Medal for her book of poems, Double Persephone. Atwood has also been a writer of feminist works such as The Edible Woman, published in 1969.

As a novelist, Atwood is a master puppeteer of dystopian theater, pulling the strings of character and scene on a macabre stage of her choosing. But her repertoire is not limited by time nor subject—she’s exquisitely adept at her craft—a frankly stunning career of writing—not only of speculative fiction like The Handmaid’s Tale and the MaddAddam Trilogy, but with novels such as Alias Grace, based on the true story of an infamous double murder in Canada during the nineteenth century.

Her latest novel, The Testaments, is told in an epistolary style via three points of view: Aunt Lydia, arguably the most powerful woman in Gilead; Agnes, a young coming-of-age woman in Gilead—a perilous journey in this male dominated sphere; and Daisy, a teenager living in Canada, who is everything that Agnes is not—but with a secret, and infamous, past.

Atwood's delicious character development is especially effective with Aunt Lydia, a central figure in The Handmaid’s Tale. Now in The Testaments, we see her fleshed out, discovering who she was before the rise of Gilead. In a reflective passage by Aunt Lydia, she asks herself:

“How will I end? I wondered. Will I live to a gently neglected old age, ossifying by degrees? Will I become my own honored statue? Or will the regime and I both topple and my stone replica along with me, to be dragged away and sold off as a curiosity, a lawn ornament, a chunk of gruesome kitsch?

Or will I be put on trial as a monster, then executed by a firing squad and dangled from a lamppost for public viewing? Will I be torn apart by a mob and have my head stuck on a pole and paraded through the streets to merriment and jeers? I have inspired sufficient rage for that.”

Her character Agnes, a young woman of Gilead, grapples with the twists and turns of political and social intrigue: “And this is not heaven. This is a place of snakes and ladders, and though I was once high up on the ladder propped against the Tree of Life, now I’ve slide down a snake.”

As the story unfolds, we are introduced to the character of Daisy, a teenager trying to unearth her mysterious past, finding herself vulnerable and confused as she parses her fate: “The world was no longer solid and dependable, it was porous and deceptive.”

Atwood leads us to the conclusion of this terrifying fictional world of Gilead, but as the curtain falls and the crowd disperses from the theater, what real world do we encounter through the exit doors?

In times of turmoil, we humans rush to elusive havens advertising peace and prosperity. But we must be on guard—perhaps the carny at the gate is simply fooling us with a ‘switch and bait’ in which we give away hard won freedoms for false promises. A timely and poignant line from The Testaments: “How much of belief comes from longing?”

This review was initially published on FUTURISM.

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

SUBSCRIBE TO K.E. LANNING TO RECEIVE BLOG ARTICLES AND AUTHOR UPDATES

What if the ice caps melted . . . in one human lifespan?