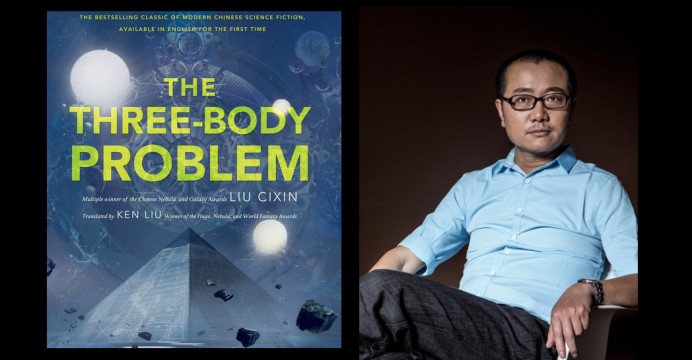

CIXIN LIU

The hottest sci-fi writer in China takes on the world...

Photo courtesy of Tor Books

Liu Cixin [writing in English under the name, Cixin Liu] is a science fiction writer from China; a nine-time winner of the Chinese Galaxy Award (Chinese Hugo) and the Xing Yun Award (Chinese Nebula), and the first Asian to win a Hugo Award, in 2015, for his work, The Three-Body Problem (translated by sci-fi author, Ken Liu, and published by Tor Books.

Now a sci-fi film has been finished for The Three-Body Problem. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZqYSpTOshVQ

So who is Liu Cixin? He was born in 1963 in Yangquan, China, during that country’s Cultural Revolution—a major influence in his life. His parents worked in a mine in Shanxi, but sent Liu to live in his ancestral home in the Henan province to escape the violence in the country. Liu was educated at the North China University of Water Conservancy and Electric Power, graduating in 1985, and then worked as a computer engineer. [primarily sourced from Wikipedia]

He’s an engineer by training, but what was the spark for Liu to write speculative science fiction?

As a scientist, a longtime reader of science fiction, and now myself a science fiction author, I embrace the idea that science and art are two sides to the same coin. In Liu’s novels, physics becomes poetry and his characters reveal vulnerable souls, lost in a shifting world they can’t truly grasp, but who remain determined to be true to themselves.

His characters travel through a procession of spectacular worlds, strung like pearls along a silk cord, harkening back to the intricate creations built by sci-fi writer, Arthur C. Clarke. Josh Rothman of The New Yorker wrote a lovely article on Liu Cixin: http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/chinas-arthur-c-clarke

Through his writings, Liu Cixin reveals an amazing mind, using science as both a physical and creative force, imagining worlds in which humans are never sure where the fate of the universe will leave them.

Cixin Liu Interview with author K.E. Lanning

You were born during the turbulent time of the Cultural Revolution in China. Your parents worked in the mines of Shanxi, but you were sent to live in the Henan province to escape the violence. Can you tell us about growing up in that difficult period in China and how it affected you as a writer?

As a child, I witnessed a great deal of violence and persecution as well as social unrest during The Cultural Revolution. These are all mass movements, which, at some point, made individuals uncontrollably crazy, just like Gustave Le Bon in The Crowd as he was described in the book. This experience has made me understand the complexity of human nature and society—I’ve realized that the future of human civilization is also full of danger and uncertainty. Such understanding is manifested in my science fiction novels like The Three-Body Problem.

Do you feel that you are a driven person and what specifically drives you?

I was quite curious about the unknown world and was full of yearnings for the vast universe, and it was this wonder and desire that drove me to write science fiction. I’ve tried to describe the relationship between man and nature and the universe, using imagination to expand my existence.

Physics is the elemental language of the universe and you weave it into your writing like poetry. Can you discuss your love of physics and the role it plays in your works?

Physics is the science to understand the fundamentals of the world and it explores the deepest mysteries of nature and the universe. The world described by modern physics has already moved far beyond our common sense and intuition, even beyond our imagination, and this is, of course, the richest resource for science fiction. I’ve tried to turn the magical world as demonstrated by modern physics into vivid stories. Most of my stories were based on and imagined along the lines of physics and cosmology.

What are the primary influences specifically in your writing, such as authors you’ve read?

The writer who has influenced me the most is Arthur C. Clarke. His 2001 Space Odyssey revealed the breadth and depth of science fiction imagination and thinking. Clarke also wrote Rendezvous with Rama, showing the ability for science fiction to create an imagined world. The entire work is like the Creator’s giant blueprint depicting an intricate world in which each brick is delicately done. Another influential writer to me is George Orwell, whose 1984 provides a panoramic description of a possible future societal state, showing the ability of science fiction literature to reflect the reality from an angle unavailable to traditional realism.

World building seems to be a central thread through your stories—what is the impulse of creating these intricate worlds?

When I was just a reader of science fiction, what attracted me most to the science fiction genre was the multitude of imagined worlds it had created, which expanded the narrow breadth of my life. Now that I have become a science fiction writer myself, “world building” has become a primary direction for writing.

Western culture experienced the rise of the individual during the Renaissance, but in Chinese culture, responsibility for the greater good of society carries more weight than the individual. Through your characters, this strand appears to carry through your work. Can you discuss this?

The liberation of humanity after the Renaissance is, of course, a huge progress for human civilization. In the modern world, it is the trend for the development of human society to be people-centered, and this is certainly a bright direction. Even in China, where there still exist various problems in this regard, it is also the general direction of development.

But what needs to be pointed out is the fact that the worlds described by science fiction are invented by the author. In the science fiction stories that I have written, there is a huge difference between the fictional world I have crafted and the real world. The fictional worlds I create are worlds in which humanity is in crisis or facing calamity, and some worlds are on the verge of extinction.

A social system is inseparable from the environment in which a society finds itself. Under such circumstances, there would need for a suitable and adaptable system. To face a calamity, it might be possible that collectivism may once again become a mainstream view on values.

Your trilogy, Remembrance of Earth’s Past, though primarily dystopian, has elements of hope, as it claws through the social and political side of human nature and our place in the universe. Is that correct and can you discuss this?

As to the future of humanity, I’m essentially an optimist. I believe that with the advancement of technology, mankind has a hopeful future. But this optimistic view is based on reason: on one hand, whether the future will be bright or be dark depends largely on the choices we make today. I think human beings are capable of finding a reasonable and correct choice for the direction of their development. Underlining that truth, the world walked away from destroying itself in a nuclear war during the last century.

But there also exists the possibility of a wrong choice. Human civilization may face all kinds of crises, which might come from changes of the Earth’s environment or from outer space, i.e., encountering extraterrestrial civilizations.

Therefore, the future in my eyes is bright, although it is full of all kinds of challenges and pitfalls. A positive future can only be obtained through human effort, striving towards the greater good.

In Death’s End, I felt a strong sense that much of the character development of Cheng Xin and Yun Tianming stem directly from you as a person. Can you comment on that?

The characters in my novels have little to do with my own life. When I was portraying these characters, I rarely put myself into them. They are more like some kind of signs or symbols and their character development is mainly dictated by the need of the story.

It’s fantastic that The Three-Body Problem has been made into a film. How do you feel about seeing your work adapted to the screen? How involved were you in the adaptation of the screenplay?

I am naturally pleased that my own novels can be made into films, but in China, we still lack experience in making science fiction movies, especially those big-budget science fiction films such as The Three-Body Problem. It’s a challenge to be successful the first time. Therefore, I take it calmly, viewing it only as a good start for Chinese science fiction movies. I have participated a lot in the shooting of the film, mainly in the areas where a science fiction writer excels, such as script production, or design of concept for special effects and other things.

Can you give us a hint of what is next for you?

I am working hard at writing my next novel, and my plan is to make the new novel different from The Three-Body Problem in terms of its theme.

With an allegorical spotlight, Liu Cixin’s trilogy of The Three-Body Problem, The Dark Forest, and Death’s End, illuminate the deep political and social issues in our world, in a desire to make sense of our common humanity and our place in the universe.

In a lyrical quote from Death’s End, Liu writes: “The ultimate fate of all intelligent beings has always been to become as grand as their thoughts.”

But the question remains—what if someone out there in the universe answers our call?

My sincere thanks to Liu Cixin for this interview, to Desirae Friesen at Tor Books, and to Hongchu Fu, for aiding in translation.

Also published at: https://futurism.media/in-the-authors-universe-interview-with-sci-fi-author-cixin-liu on May, 2017

K..E. Lanning, Author of: