Hot News for Hot Times...

News Flash for the masses huddling in A/C on this July day of 2024 with the Misery level in triple digits…

Posters for In the Wilderness and Where the Sky Meets the Earth

My short screenplay, In the Wilderness (a scene out of my Where the Sky Meets the Earth miniseries) is a TOP FINALIST in the Richmond International Film Festival!! And to sweeten the pot, the pilot screenplay for the miniseries, Where the Sky Meets the Earth, was also honored as a Semi-finalist in the Richmond International Film Festival -- WOOHOO! Many thanks to the judges, RIFF, and especially my awesome critique group, Virginia Screenwriters' Forum!!!

Lost in the Time of Covid

COVID finally caught me in the spring of 2022. The virus gripped me in a malaise of fatigue and pain—and despair. Surging blood pressure, coughing until my chest ached, exhaustion and brain fog—all demanding that I rest, rest, rest. Many nights, as I lay in bed, I would imagine and then reimagine scenes in my half-completed manuscript. But, as I tossed and turned, I wondered—would I live to finish this novel? Or would I die, leaving my words stranded? Days merged into weeks . . . and then months.

Sick and weak, I lay in my room, gazing at the changing nature outside my window. In April, the winds rolled like waves, the moan of each gust rising as it approached, bowing branches with tender leaves, showering pollen in its wake. In May, the leaves stretched to full length, trembling in passing breezes. In June, emerald leaves hung listless until puffy clouds gathered, then darkened and raced across the sky, heralding their arrival with bursts of lightning and growls of thunder, pummeling the earth with rain.

Somehow, it seemed appropriate that I read Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time.

In Search of Lost Time

Written in the first person, Marcel Proust’s prodigious multi-volume novel is regarded as a loose version of his own life. The story begins with the narrator as a young boy, retiring early to his bed, listening to parties outside his room, and desperately missing his mother’s presence.

As the story unfolds, the narrator describes life in the fictional town of Combray believed to be modeled after the real village of Proust’s own childhood, Illiers, renamed in 1971 to Illiers-Combray in his honor. With lyric prose, he takes us with his family along walks through the village and countryside.

“…we would be met on our way by the scent of his lilac-trees, come out to welcome strangers. Out of the fresh little green hearts of their foliage the lilacs raised inquisitively over the fence of the park their plumes of white or purple blossom, which glowed, even in the shade, with the sunlight in which they had been bathed.”

Proust wrote visually. The reader yields to his immersive, detailed images, seen from the narrator’s eyes, of the beauty of the landscape, his daily encounters with family and friends, and the varied rooms in which he lives. And his tangled relationship with life itself.

But overshadowing the narrator, from childhood through his final days, is a debilitating asthma—each breath precious and illusive. The same disease which plagued Proust himself. He spent his last years confined to his bedroom, sleeping during the day and working at night on his novel. In 1922, one hundred years ago, Marcel Proust died of pneumonia at the age of fifty-one.

The Light at the End

An excerpt from Volume II, Within a Budding Grove, resonated with my state of mind as I finally imaged the light at the end of COVID:

“Once again I had escaped from the impossibility of sleeping, from the deluge, the shipwreck of my nervous storms. I feared now not at all the menaces that had loomed over me the evening before, when I was dismantled of repose. A new life was opening before me; without making a single movement, for I was still shattered, although quite alert and well, I savored my weariness with a light heart; it had isolated and broken asunder the bones of my legs and arms, which I could feel assembled before me, ready to cleave together, and which I was to raise to life merely by singing, like the builder in the fable.”

As the grass withers in the summer of 2022, I have returned to writing my novel, fed, in part, by hazy revisions in those midnight hours.

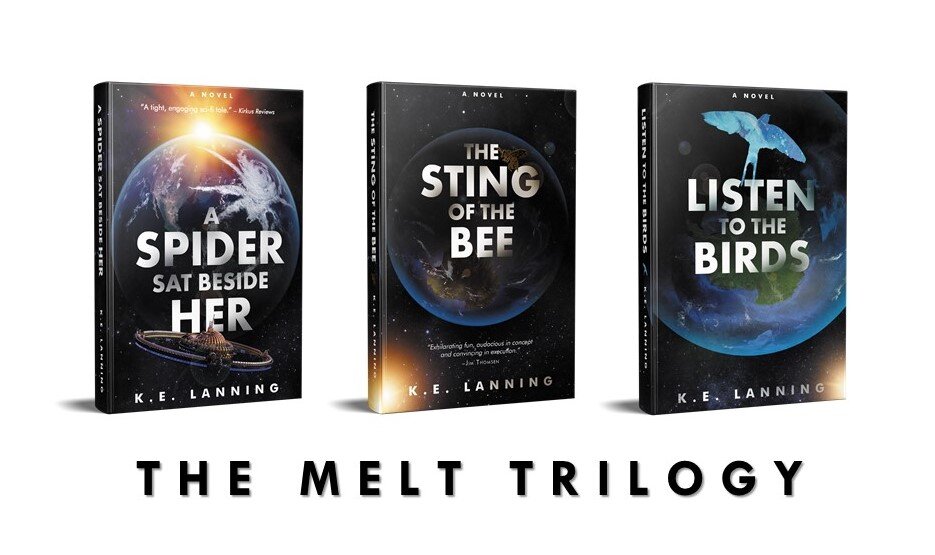

Karen (K.E.) Lanning www.kelanning.com , author of the cli-fi series, The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds, and currently writing two commercial literary novels: Where the Sky Meets the Earth and The Light of the Sun.

Review of Claire Vaye Watkins's novel, 'I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness'

I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness is Claire Vaye Watkins’s latest novel, [released October 5th, 2021] and is written in the form of a memoir interlaced with her family saga—one can imagine a tattered journal, interwoven with detritus from past and present, pages scrawled in a corner of the Vegas airport or under the branches of a Joshua tree, its cover cracked from the heat of the desert—stories of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll and vagina dentata—what more could you want?

Bio

Born in Bishop, California in 1984, Watkins grew up in the Mojave Desert on the fringe of Death Valley—first in Tecopa, California and then Pahrump, Nevada, living in a desert landscape of sand and gravel, yucca and mesquite, edged by the gray chiseled Nopah Range—the extremes of life and death of nature in striking distance of the fantasyland of Vegas. But Watkins’s unique upbringing was not only the desert—her father was Paul Watkins, a member of the Charles Manson Family. By illuminating Manson’s “Helter Skelter” motive, he ultimately brought Manson to justice after the horrific Tate and LaBianca murders in Los Angeles. Watkins describes her mother, Martha, as “a great bullshitter” and “incredible dynamo” who found a way to survive in a grueling world. Her parents met at the Crowbar bar on the edge of Death Valley, married, and had two daughters, Claire and Lise Watkins.

Watkins received her Bachelor’s degree from the University of Nevada, Reno and her Master of Fine Arts from Ohio State University. She has taught at Princeton and Bucknell universities, and was an assistant professor at the Helen Zell Writers’ Program at the University of Michigan. Currently, Claire Vaye Watkins teaches creative writing at the University of California, Irvine.

Literary Debut

Watkins made her literary debut in 2012 with a collection of short stories, Battleborn, earning literary accolades on multiple fronts. The New York Times called the collection, “brutally unsentimental,” and The New Yorker wrote that Watkins is writing in an entirely new genre: “Nevada Gothic.” Battleborn won The Story Prize, The Dylan Thomas Prize, the New York Public Library Young Lions Fiction Award, The Rosenthal Family Foundation Award and The Silver Pen Award from the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame. She has been published in a slew of respected publications: Granta, Tin House, Freeman’s, The Paris Review, Story Quarterly, New American Stories, Best of the West, The New Republic, The New York Times, and Pushcart Prize XLIII, to name a few. Watkins was included in the National Book Foundation’s “5 under 35,” Granta’s “Best Young American Novelists,” and awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Her first novel, Gold Fame Citrus, published in 2015 by Riverhead, is a work of stunning speculative fiction, and hit the literary scene with a flurry of critical praise, named the Best Book of the Year by a host of publications: The Washington Post, NPR, Vanity Fair, LA Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Huffington Post, The Atlantic, Refinery 29, Men's Journal, Ploughshares, Lit Hub, Book Riot, Los Angeles Magazine, Powells, BookPage, and Kirkus Reviews.

The near future story is set on a West Coast suffering extreme drought with shifting sand dunes driving out all but the dregs of society, who, like rats, rifle through the scraps of the rich and famous who have fled the Golden State. As the main characters flee eastward from California, they discover a tribe in the desert—a commune of the insane, the desperate, and the unlucky—led by an enigmatic master.

Watkins’s dystopian parable weaves metaphor and angst as desperate and tenuous humans cling to life within oceans of sand. With vestiges of Orwell and LeGuin, she scatters her disturbing “Alice in Wonderland” existence with peculiar and broken characters, irrevocably wounded by life.

I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness

If Gold Fame Citrus can be described as intensely surreal, then Watkins’s latest novel, I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness, is a foil in a way—the brutal realism of life. Primarily told in the first person, the story has a disjunctive feel: Claire’s anguished memoir, jumbled with stories from her father’s past, and, in reverse chronological order, her mother’s old letters to her cousin Denise, inserted at random places, as if tucked within the pages of a book.

The novel begins after the birth of the main character’s first child, and Claire sinks into a quicksand of post-partum depression, and attempts to persuade herself that this will pass.

“I would be okay—would survive my child’s first winter, a sludgy era of despair, bewilderment, and rage passed in the palm of the mitten.”

As Claire tries to come to terms with her life, she recalls the stark grief of losing Jesse, a lover from her past, in a wreck:

“There is a shattered windshield, a cop car, an ambulance, a fire engine tilted on the soft shoulder of the highway, lights blazing. The sun is rising and the mountains are indigo above you. Someone has tucked you up so none of you is showing so we don’t have to see the parts of you we don’t want to.

You were here, then you were gone.”

Watkins peppers a wry and, at times, bitter humor within her narrative, and yet the novel’s essential humanity is poignantly revealed in Claire’s attempt to understand the dysfunctional love of her family:

“We have loved and loved and been loved despite the fissures and loses, violence, cruelty, smallness, timing, deficits in money and time and attention, despite the betrayals and indifferences, the distance and weather, despite developing different definitions of certain words. Death, expensive, cold.”

There is a deep, stark honesty in I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness—where one finds comfort in the shadows—hiding from the vulnerability and powerlessness of love. Though life can be beautiful, it’s also a journey through a valley of heartache, sorrow, and loss—and at its deepest abyss—a place where fear trumps love. As the old expression goes, perception is everything, but in our flawed myopic vision, is what we think we see real, or is the world simply a chaotic and surreal mirage? I guess it depends on how good the drugs are…

Please check out my fantastic interview with Claire Vaye Watkins on The Millions.

Additional links to I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/668168/i-love-you-but-ive-chosen-darkness-by-claire-vaye-watkins/

https://bookshop.org/books/i-love-you-but-i-ve-chosen-darkness/9780593330210

Karen (K.E.) Lanning www.kelanning.com , author of the cli-fi series, The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds, and currently writing two commercial/literary novels: Where the Sky Meets the Earth and The Light of the Sun.

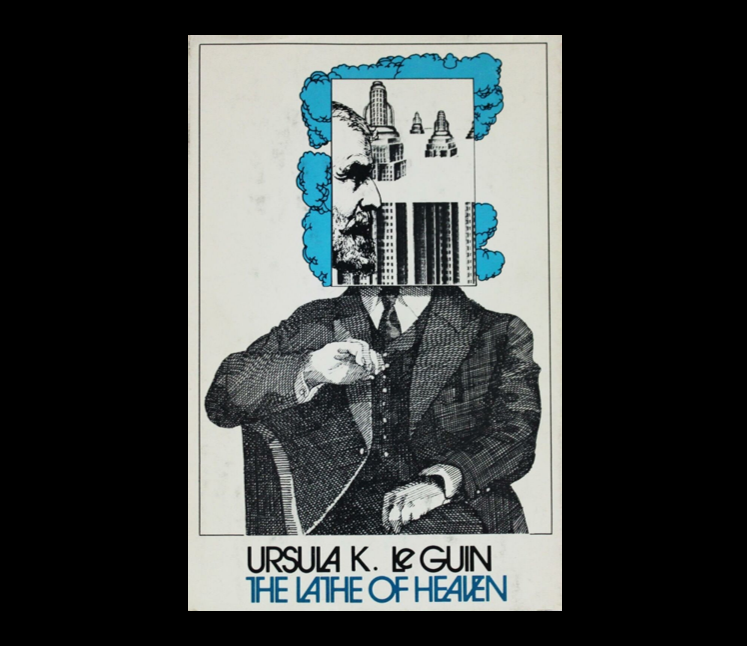

Ursula K. Le Guin's 'The Lathe of Heaven' on its Fiftieth Anniversary

Original Hardcover of Lathe of Heaven - 1971

Ursula K. Le Guin’s novels defy classification as to whether they are speculative fiction or simply literary fantasy—her exquisite prose creating rich tapestries, surreal dreams of plot and character, woven with fierce threads of social and philosophic commentary.

The Lathe of Heaven was published in 1971, following her blockbuster success with her 1969 novel, The Left Hand of Darkness, but Le Guin’s writing career began in the late 1950’s, strongly influenced by cultural anthropology, Taoism, feminism, and the writings of Carl Jung.

The title, The Lathe of Heaven, is taken from the writings of Chuang Tzu (Zhuang Zhou), a passage from Book XXIII, paragraph 7, quoted as an epigraph to Chapter 3 of the novel:

“To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven.”

Le Guin chose the title because she loved the quotation. However, it seems that the quote is a mistranslation of Chuang Tzu's Chinese text. In an interview with Bill Moyers recorded for the 2000 DVD release of the 1980 adaptation, Le Guin clarified the issue:

“...it's a terrible mistranslation apparently, I didn't know that at the time. There were no lathes in China at the time that that was said. Joseph Needham wrote me and said "It's a lovely translation, but it's wrong."

Regardless of the misinterpretation of the original text, the title stands as a singularly powerful concept.

The Lathe of Heaven

The story is set in Portland, Oregon, in 2002, in a world devastated by global warming, poverty due to overpopulation, and Middle East wars. The protagonist, George Orr, is a draftsman who abuses drugs in an attempt to stifle his ability to dream—he has discovered, to his abject terror, that when he dreams “effective” dreams, they alter reality; however, he is the only one who recalls the previous reality. Because of his illegal drug abuse, he is forced to undergo “voluntary” psychiatric care under a psychiatrist and sleep specialist named William Haber. Haber discovers that he can influence George’s dreams and becomes a type of puppet master over him, manipulating reality to “save the world”, but also enhance Haber’s wealth and status. Under Haber’s machine, the Augmentor, he uses George’s power to “do good” but he cannot control George’s dreams, and bizarre, twisted realities ensue. George realizes Haber’s dubious plan and enlists a lawyer, Heather Lelache, to represent him against Haber’s scheme, with limited success as reality continues to be altered, including her own existence.

The novel was initially serialized in the American science fiction magazine Amazing Stories. The novel received nominations for the 1971 Nebula Award, the 1972 Hugo, and won the Locus Award for Best Novel in 1972. The novel was adapted to film by PBS and released in 1980 with Le Guin involved in the production of the adaptation. A second adaptation was released in 2002; however discarding a significant portion of the story.

Ursula K. Le Guin

Born Ursula Kroeber in Berkeley, California, 1929, she grew up on the Pacific Coast, immersed in anthropologic worlds through her father, tales handed down through her family, and classic literature. Le Guin graduated from Radcliffe in 1951, married historian Charles Le Guin in 1953 and they had three children, Elisabeth, Caroline, and Theodore. In 1959, the family settled in Portland as their permanent residence.

During an interview with Mark Wilson, Le Guin discusses her early influences: “Once I learned to read, I read everything. I read all the famous fantasies – Alice in Wonderland, and Wind in the Willows, and Kipling. I adored Kipling's Jungle Book. And then when I got older I found Lord Dunsany. He opened up a whole new world – the world of pure fantasy. And ... Worm Ouroboros. Again, pure fantasy. Very, very fattening. And then my brother and I blundered into science fiction when I was 11 or 12. Early Asimov, things like that. But that didn't have too much effect on me. It wasn't until I came back to science fiction and discovered Sturgeon – but particularly Cordwainer Smith. ...I read the story Alpha Ralpha Boulevard, and it just made me go, "Wow! This stuff is so beautiful, and so strange, and I want to do something like that."

In the 1960s, Le Guin found her voice through science fiction, publishing her first novel, A Wizard of Earthsea in 1966. By 1970, she had won the Hugo and Nebula awards for The Left Hand of Darkness [1969] an exquisite novel exploring gender and the concept of “otherness”. In the year following, Robert Heinlein published his novel, I Will Fear No Evil [1970] exploring male and female sexuality, but he never crossed the boundary into the deconstruction of gender like Le Guin's brilliant concept in The Left Hand of Darkness—the idea that gender is not absolute, but ephemeral. Jo Walton at Tor Books wrote a lovely article on The Left Hand of Darkness and Le Guin: Gender and glacier: Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness

With multiple awards in her literary career, Le Guin is considered one of the greatest speculative fiction writers of all time. Over her career, she received numerous accolades, including eight Hugos, six Nebulas, and twenty-two Locus Awards, and in 2003 became the second woman honored as a Grand Master of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. In 2000, the U.S. Library of Congress named her a Living Legend, and she won the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 2014. Le Guin has influenced many other authors, including Booker Prize winner Salman Rushdie, David Mitchell, Neil Gaiman, and Iain Banks. After her death in 2018, critic John Clute wrote that Le Guin had "presided over American science fiction for nearly half a century", and author Michael Chabon referred to her as the "greatest American writer of her generation".

Ursula K. Le Guin, photo credit Jack Liu

In 2016, Julie Phillips wrote a superb article on Le Guin for the New Yorker: The Fantastic Ursula K. Le Guin, including an intimate conversation with Le Guin at her Portland home.

Le Guin died on January 22, 2018 at the age of 88, but her literary heritage will continue to influence, be it bur or spur, on our society. I leave you with a prescient quote from Ursula K. Le Guin in 2014:

“I think hard times are coming when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies. We will need writers who can remember freedom. Poets, visionaries – the realists of a larger reality.”

—Ursula K. Le Guin

Many thanks to Wikipedia for background of Ursula K. Le Guin and to interviewers: Mark Wilson, Jo Walton of TOR, and writer Julie Phillips, contributor to The New Yorker.

K.E. Lanning, author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds; and her upcoming novel: Where the Sky Meets the Earth.

This article was also published on FUTURISM on January 7, 2021.

A Ruthless World?

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, photo courtesy of Lynn Gilbert

Speculative fiction asks the question, “What if?” But in the real world, what if Ruth Bader Ginsburg had not existed? Would the dystopia of Margaret Atwood’s Hand Maid’s Tale be knocking at our door? It’s hard to know the butterfly effect of such a scenario on our modern society, but we do know, and have lately seen, how the dark forces of authoritarian dominance can destroy our civil liberties. Bold in her approach and tenacious in truth, Ruth stands with the giants in the crusade for freedom of the individual, not just freedom for women, but for every human being, because civil rights for one, spreads to all.

The Renaissance is viewed as a time for great art and science, but the true paradigm shift was a spark of consciousness—the individual is significant and each human being has worth and weight in this world. From the early Greek experiment to the radical idea that human beings have universal natural rights to liberty and essence, we’ve carved our democratic principles and rules of law. The individual right to vote—no matter the color of your skin or your gender—took centuries of blood, sweat, and tears.

But it took a woman, small in stature and quiet of voice, to take on the Supreme Court of the United States to achieve equality for a human being who is, simply by chance, a woman.

K.E. Lanning

Author of The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

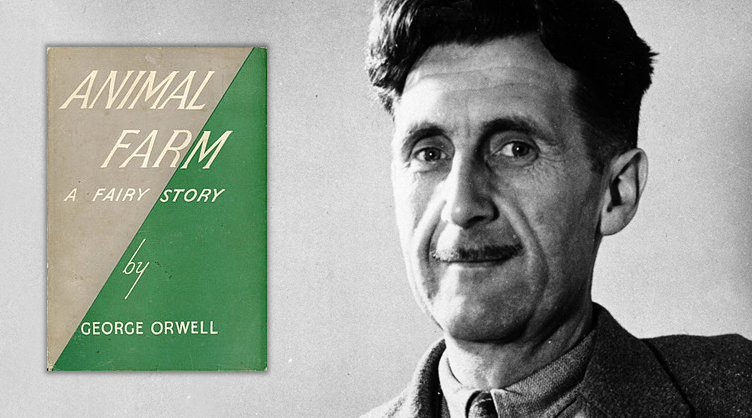

Animal Farm – 75th Anniversary and chillingly relevant

First edition cover (1945) for Animal Farm and author George Orwell

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others. Animal Farm, 1945

In the preface of the allegorical novella, Animal Farm, Orwell described the source of the idea of setting the book on a farm:

“...I saw a little boy, perhaps ten years old, driving a huge carthorse along a narrow path, whipping it whenever it tried to turn. It struck me that if only such animals became aware of their strength, we should have no power over them, and that men exploit animals in much the same way as the rich exploit the proletariat.”

Orwell began writing Animal Farm in March of 1943 and completed it in April 1944. Several publishers refused it, considering it an attack on the Soviet regime and, despite Stalin’s murderous purges, Russia was a crucial ally during WWII. Finally published on August 17th, 1945, Animal Farm resonated in the post-war era, achieving worldwide success, and Orwell became a celebrated figure.

Orwell described Animal Farm as a “fairy story” or fable reflecting the Russian Revolution and Stalinist era of the Soviet Union. The book weaves a story of farm animals who, led by two pigs, Snowball and Napoleon, rebel against their human farmer and attempt to create their own free and equal society. Power mad, Napoleon overthrows Snowball and the utopian society devolves into a dictatorship, with Napoleon now indistinguishable from the human owner the animals had ousted. Animal Farm was the first book in which Orwell tried, “to fuse political and artistic purpose into one whole.”

ORWELL’S EARLY LIFE

George Orwell was born Eric Arthur Blair on June 25th, 1903 in Motihari, India. He grudgingly attended Eton, and though not a stellar student, he was known as a practical joker and a young man who argued for argument sake. In 1922, he sailed to Burma and worked as a police officer until he contracted dengue fever in 1927, after which he returned to England. At this point, among a variety of occupations, he began his writing career, but Orwell’s tenuous health would continue to plague him for the rest of his life. Inspired by the River Orwell in Suffolk, England, he took on the pen name George Orwell in 1933 for the publication of his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London.

In 1936, Orwell went to fight against Fascism in the Spanish Civil War, but over time, he became disillusioned with the Communists, and after he and his wife escaped from Spain, he considered himself forced into the role of pamphleteer. “The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.”

ORWELL THE WRITER

Contemporaries of Orwell paint the picture of a man who struggled to become a writer through long periods of poverty, failure, and humiliation, but he turned the sweat and agony into literature [paraphrased from Fyvel]. Ben Wattenberg stated: "Orwell's writing pierced intellectual hypocrisy wherever he found it." According to historian Piers Brendon, “‘Orwell was the saint of common decency who would in earlier days,’ said his BBC boss Rushbrook Williams, 'have been either canonised—or burnt at the stake'"

In 1940, Orwell wrote: "The writers I care about most and never grow tired of are: Shakespeare, Swift, Fielding, Dickens, Charles Reade, Flaubert and, among modern writers, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot and D. H. Lawrence. But I believe the modern writer who has influenced me most is W. Somerset Maugham, whom I admire immensely for his power of telling a story straightforwardly and without frills." Elsewhere, Orwell strongly praised the works of Jack London, especially his book, The Road.

He wrote an essay in 1946, “Why I Write,” in which he details his journey to writing. He professes four motives for writing:

1. Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful business men – in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they abandon individual ambition – in many cases, indeed, they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all – and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.

2. Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.

3. Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.

4. Political purpose. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people’s idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

And yet Orwell famously said, “Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness.”

First Edition cover (1949)

In 1949, George Orwell went on to publish his best-known work, Nineteen Eighty-Four, a dystopian novel of government repression and overreach. He created a terrifying world in which the citizenry is trapped in a constant state of fear of unending wars versus “others” and controlled by surveillance and propaganda. The unnerving echo of political manipulation of the truth tolls like a bell across our world.

Orwell died from tuberculosis in 1950 at the age of forty-six, but his profound tales of totalitarianism are still relevant in their searing exposure of today’s societal ills.

IN THE YEAR 2020

On the seventy-fifth anniversary of Animal Farm, we’ve made progress on civil rights, women’s rights, and LGBTQ rights—and yet the rich and powerful are still “more equal” than others. How can this be? Where is the line between political satire and reality in our new millennium?

Inequality suits the powerbrokers, and so the deep-seated irrational fears of race, misogyny, sexual orientation and xenophobia are exploited by clever puppet masters in order to maintain control. And why Margaret Atwood’s chilling novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, has struck a deep chord within our not-so-perfect union in America and the world.

The sad truth of human nature is that bigotry is a cudgel of dominance—Orwell’s Animal Farm endlessly played out in real life, enabling a machine of intolerance—an institutional hierarchy. For those who doubt this system of privilege and power exists, just look into the eyes of Derek Chauvin as he coldly executes George Floyd—he knew was protected by this supremacy. Orwell’s words haunt us to this day: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

August 17th, 2020

K.E. Lanning, author of The Melt Trilogy

My in-depth interview with Margaret Atwood (audio version at top).

Many thanks to Wikipedia and The Orwell Foundation for background on George Orwell.

This article was also published on FUTURISM.

Perdido Street Station—the 20th anniversary of China Miéville’s critically acclaimed novel.

Where Fiction gets Weird

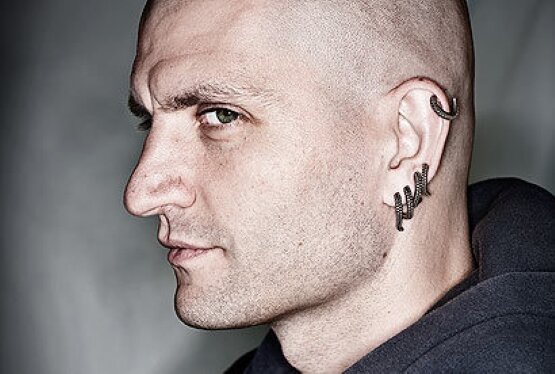

Author China Miéville, photo courtesy of Mic Cheetham Agency

Celebrating its twentieth anniversary, China Miéville’s award winning Weird/urban fantasy novel, Perdido Street Station (2000, Macmillan), is the opening salvo of his fictional world of Bas-Lag, a strange slurry of magic, steampunk, and post-modern enigmas. The second novel in the trilogy, The Scar, was published in 2002, and the final book, Iron Council (2004), completes the New Crobuzon trilogy.

China Miéville has received multiple awards for his works: the Arthur C. Clarke Award (three times), the World Fantasy Award, the British Fantasy Award (twice), the Hugo Award, the Locus Award (four times), the Kitschies, the BSFA Award and multiple nominations for various literary awards, including the prestigious Nebula Awards. His most notable works are: Perdido Street Station, The City & The City (2009), and Embassytown (2011), winner of the Locus Award for Best Science Fiction Novel in 2012. The City & The City, particularly relevant to our current political and social chaos, was adapted for a BBC television series in 2018:

Miéville sites multiple authors as influences in his writing, most notably, M. John Harrison, Mervyn Peake, Michael de Larrabeiti, and Ursula K. Le Guin. Miéville’s debut novel was King Rat (1998), an urban fantasy novel set in London during the end of the twentieth century, and nominated for both the Bram Stoker Award and the International Horror Guild Award in their First Novel category. Within the spectrum of fantasy writings, Miéville is firmly on the urban surrealism end as opposed to the Tolkien end of the genre. He is a prolific writer, not afraid to cross genres, and terms his novels simply as “Weird Fiction.”

So who is the illusive China Miéville? Besides being a fantasy fiction writer, he’s political activist, and an academic. Miéville was born in Norwich, England in 1972 and spent most of his early years in northwest London. His first name, China, springs from his parents’ desire for a beautiful first name, perusing a dictionary until they found the word China. His father left after his birth and he was raised by his American mother, Claudia, a writer, translator, and teacher. He credits playing Dungeons & Dragons as a youth for influencing the fantastical premise of his novels.

Miéville attended Oakham School in Rutland, England, and after graduation, taught English in Egypt for a year, developing an interest in Middle Eastern culture and politics. He received an undergraduate degree in social anthropology at Clare College in 1994, then a masters and PhD in international relations from the London School of Economics in 2001. During his graduate studies, he became disillusioned with materialistic aspects of capitalism and became a Marxist. His political bones become subtle threads within his novels, highlighting the abuse of power, bigotry, and the stratification of economic classes within society.

Perdido Street Station launched Miéville onto the sci-fi fantasy stage with creatures so detailed in their descriptions that you can almost feel the drool on the page. Miéville pings the end of the spectrum of ‘exotic’ in his sculpting of creatures, adding a dimension with his Remades, a cast of surgically altered beings. Beneath the rustle of feathers and the skin prickling insect-humanoids, are there metaphorical intentions of his creatures? Though Miéville distances himself from overt political content, eddies of social commentary lie beneath the surface. Miéville explores the human condition as his main character, Isaac, faces racism in his relationship with Lin, an exo-skeletal humanoid, while veins of corruption ooze through the city of New Crobuzon. In Perdido Street Station, the Construct Council, a sentient machine comprising myriads of small appliances (a corporate entity?), manipulates subtle control within the city, but ultimately helps in the fight against a monstrous species of deadly slakemoths.

The enduring success of Miéville’s works underscores a deep hunger for Weird fiction, a genre rooted in the works of Edgar Allan Poe. In the angst of the 1990s, Weird fiction met urban fantasy, and in 2002, in the introduction to China Miéville's novella, The Tain, M. John Harrison is credited with creating the term "New Weird." Rose O'Keefe of Eraserhead Press claims that "People buy New Weird because they want cutting edge speculative fiction with a literary slant.” Authors Jeff and Ann VanderMeer define the New Weird genre in their introduction to the anthology, The New Weird, as "a type of urban, secondary-world fiction that subverts the romanticized ideas about place found in traditional fantasy, largely by choosing realistic, complex real-world models as the jumping-off point for creation of settings that may combine elements of both science fiction and fantasy."

Miéville takes Weird fiction to its illogical and glorious end, taking our breaths away with his incredible worlds of urban fantasy. Perdido Street Station released twenty years ago? It seems like yesterday…

Author of: The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

Author K.E. Lanning Interview on PBS for The Melt Trilogy

Sharing a novel with readers is one of the best parts of being an author! I was privileged to be asked by my local PBS station to do an interview for The Melt Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds. So gentle readers, without further ado, here’s the interview which first aired on 1/14/2020:

I hope you enjoy it, and please forward as you will! Link url: https://www.pbs.org/video/write-around-the-corner-k-e-lanning-x8easy/

Now I have to get back to finishing my next novel, Where the Sky Meets the Earth - my editor awaits!

Best wishes for 2020 and welcome to a new decade!

K.E. Lanning

Review of Author Margaret Atwood's "The Testaments"

Author Margaret Atwood (photo credit: Liam Sharp)

Master Puppeteer of Dystopian Theater

“Praise be!” It has been thirty-four years since the controversial, and even banned novel, The Handmaid’s Tale was published (1985), and on September 10, 2019, Margaret Atwood published its sequel, The Testaments. Her latest novel has already garnered critical praise and was named to the shortlist for the Booker Prize.

In The Testaments, her characters bear witness to the inevitable corruption of power in the totalitarian regime of Gilead. Extreme societies tend to end extremely, and as phrased succinctly by Gilead's Aunt Lydia: “In time like ours, there are only two directions: up or plummet.”

The Handmaid’s Tale introduced us to the country of Gilead—a nation based on strict theocracy, and though the interlude has been long, the final act of the play is The Testaments, in which we observe the increasingly corrupt machinations of a state, or perhaps a twisted royal court, which hasn’t as yet recognized its internal wounds, bleeding away the strength of its original “truths.”

Margaret Atwood, born in Ottawa, Canada in 1939, knew by the age of sixteen that writing would be her profession. Atwood graduated in 1961 with a Bachelor’s degree in English from Victoria College in the University of Toronto, and in 1962, received a Master’s Degree from Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA. In 1961, she won the E.J. Pratt Medal for her book of poems, Double Persephone. Atwood has also been a writer of feminist works such as The Edible Woman, published in 1969.

As a novelist, Atwood is a master puppeteer of dystopian theater, pulling the strings of character and scene on a macabre stage of her choosing. But her repertoire is not limited by time nor subject—she’s exquisitely adept at her craft—a frankly stunning career of writing—not only of speculative fiction like The Handmaid’s Tale and the MaddAddam Trilogy, but with novels such as Alias Grace, based on the true story of an infamous double murder in Canada during the nineteenth century.

Her latest novel, The Testaments, is told in an epistolary style via three points of view: Aunt Lydia, arguably the most powerful woman in Gilead; Agnes, a young coming-of-age woman in Gilead—a perilous journey in this male dominated sphere; and Daisy, a teenager living in Canada, who is everything that Agnes is not—but with a secret, and infamous, past.

Atwood's delicious character development is especially effective with Aunt Lydia, a central figure in The Handmaid’s Tale. Now in The Testaments, we see her fleshed out, discovering who she was before the rise of Gilead. In a reflective passage by Aunt Lydia, she asks herself:

“How will I end? I wondered. Will I live to a gently neglected old age, ossifying by degrees? Will I become my own honored statue? Or will the regime and I both topple and my stone replica along with me, to be dragged away and sold off as a curiosity, a lawn ornament, a chunk of gruesome kitsch?

Or will I be put on trial as a monster, then executed by a firing squad and dangled from a lamppost for public viewing? Will I be torn apart by a mob and have my head stuck on a pole and paraded through the streets to merriment and jeers? I have inspired sufficient rage for that.”

Her character Agnes, a young woman of Gilead, grapples with the twists and turns of political and social intrigue: “And this is not heaven. This is a place of snakes and ladders, and though I was once high up on the ladder propped against the Tree of Life, now I’ve slide down a snake.”

As the story unfolds, we are introduced to the character of Daisy, a teenager trying to unearth her mysterious past, finding herself vulnerable and confused as she parses her fate: “The world was no longer solid and dependable, it was porous and deceptive.”

Atwood leads us to the conclusion of this terrifying fictional world of Gilead, but as the curtain falls and the crowd disperses from the theater, what real world do we encounter through the exit doors?

In times of turmoil, we humans rush to elusive havens advertising peace and prosperity. But we must be on guard—perhaps the carny at the gate is simply fooling us with a ‘switch and bait’ in which we give away hard won freedoms for false promises. A timely and poignant line from The Testaments: “How much of belief comes from longing?”

This review was initially published on FUTURISM.

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

SUBSCRIBE TO K.E. LANNING TO RECEIVE BLOG ARTICLES AND AUTHOR UPDATES

What if the ice caps melted . . . in one human lifespan?

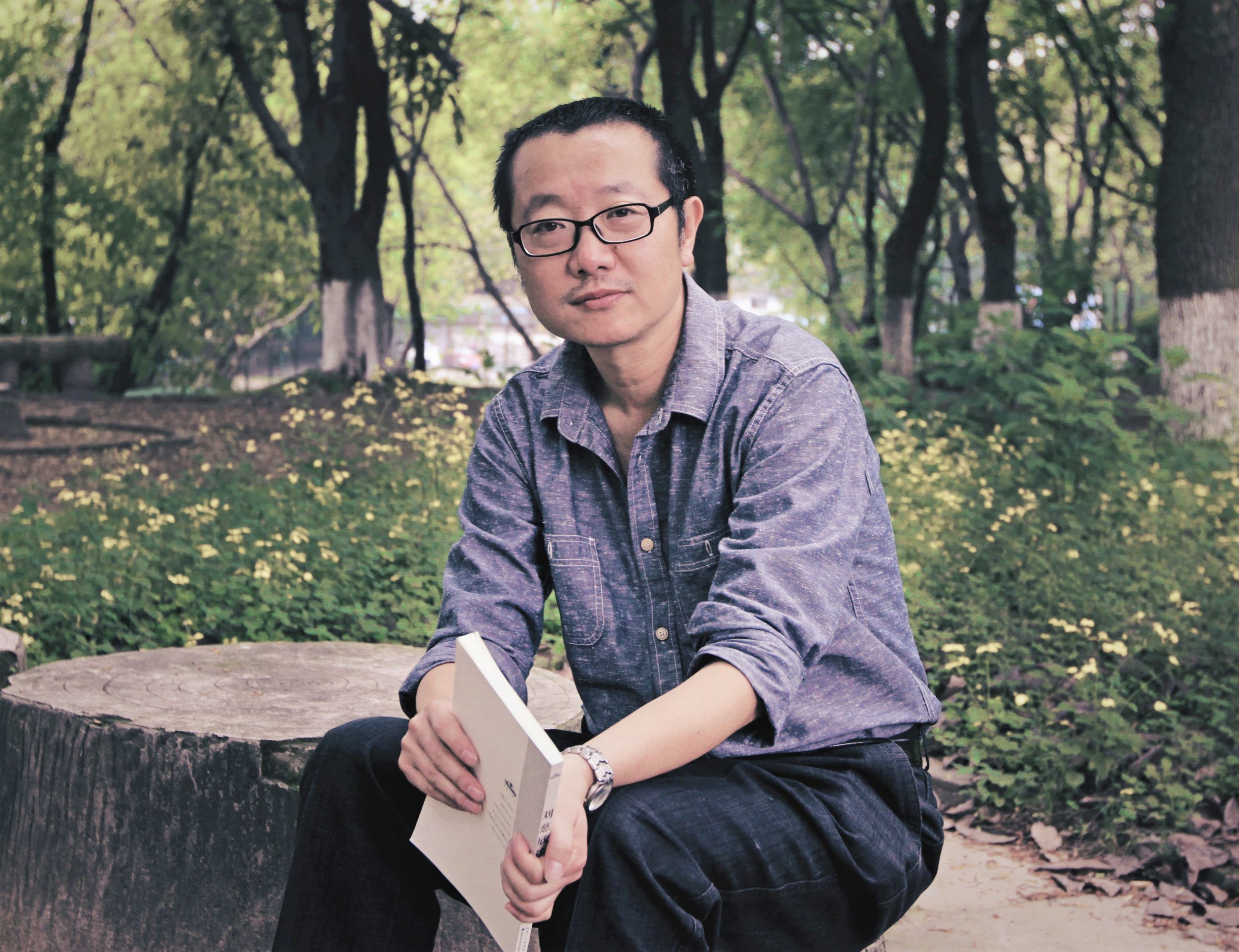

Review of Author Cixin Liu's "Supernova Era"

Author Cixin Liu

A different side of China's Revered Sci-Fi Author

Cixin Liu’s latest work, Supernova Era (launching this October & published by Tor Books), begins with a terrifying event—eight light-years from Earth, a dying star explodes into a supernova. Undetected by the world’s astrophysicists, the Earth takes a direct hit from massive waves of radiation, with disastrous effects rippling across the globe.

Though many of the fauna and flora of the Earth wither, miraculously, the chromosomes of children thirteen years and younger are unaffected, and the dying parents discover their children will survive the maelstrom. But what happens when children inherit the Earth?

For readers not familiar with Liu Cixin (publishing under the name Cixin Liu), he burst onto the western scene with his novel, The Three-Body Problem, by winning the Hugo Award in 2015, the first Asian writer to snag the award. The novel was also a 2015 Campbell Award finalist and garnered a nomination for the 2015 Nebula Award. In China, his works have received multiple awards and he has risen to be one of the leading voices in Chinese science fiction. He cites Author C. Clarke's intricate world-building as a major influence in his works.

Liu was born in 1963 (Yangquan, China) during the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution—a major impact on his life. Liu was educated at the North China University of Water Conservancy and Electric Power, and then worked as a computer engineer. [primary source: Wikipedia]

Liu’s artistic side blends seamlessly with his engineering chops. In his hands, physics becomes a palette of color and texture—he illustrates the supernova’s impact on the world in poetic prose: “... its light scattered in the atmosphere, turning it into an enormous, blinding, poison spider hanging in the western sky.”

However, unlike his Remembrance of the Earth’s Past Trilogy, Liu’s Supernova Era reveals another side of this creative science fiction author as he spins a tale, written like a history book, of how a random stellar occurrence kills off the adults of the planet, leaving the children to run the world.

Excerpts from the book:

In those days, Earth was a planet in space.

In those days, Beijing was a city on Earth.

On this night, history as known to humanity came to an end.

Influenced by writers such as George Orwell and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (written as a reaction to World War II), Supernova Era takes on a nightmarish societal treatise. Liu wrote the novel in 1989 while in Beijing just before the Tiananmen Square massacre. He describes that night:

In June of that year [1989] I was in Beijing, a city in the midst of political turmoil, and on the night of June 4, I listened in my hotel to the chaotic noise outside, and the muffled sounds of gunfire. That night I dreamed of a limitless expanse of snow, whipped up by the wind into a ground blizzard, and an object—perhaps the sun or a star—glowing with a blinding blue light that painted the sky an eerie color between purple and green. And beneath that dim glow, a formation of children advanced across the snowy ground, white scarves wrapped around their heads, rifles fitted with gleaming bayonets, singing some unrecognizable song as they moved forward in unison. . . . When I recall the horror of that grim scene it still gives me palpitations. I awoke in a cold sweat and couldn’t get back to sleep, and that’s when the germ of the idea for Supernova Era first took shape.

In Supernova Era, an innocent child’s voice recites the terror of a chaotic world held hostage by puerile leaders. Though Cixin Liu writes from a Chinese perspective, his stories highlight the universality of the human experience—the darkness and light—the love and fear—that exist within us all.

Supernova Era was translated into English by Joel Martinsen.

This review was initially published on FUTURISM: Review of Author Cixin Liu's 'Supernova Era'

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

SUBSCRIBE TO K.E. LANNING TO RECEIVE BLOG ARTICLES AND AUTHOR UPDATES

What if the ice caps melted . . . in one human lifespan?

Deep Break

“Deep Break” is an antiquated method of plowing when the soil is overturned and exposed in the early spring to ready the soil for new growth. As I construct my work-in-progress, Where the Sky Meets the Earth, I, too, dig for roots deep in history to create my novel, gathering research to develop both plot and character.

Where the Sky Meets the Earth is a work of literary fiction delving into the consequences of the recent economic fallout entangled with a perceived second coming of a messiah (think a twist on Stranger in a Strange Land set during the Great Recession). A nuclear family has exploded—unemployment, opioid addiction, and divorce. The son, a fourteen-year-old mixed-race boy, disappears into the mountains of Wyoming, seeking a true way of living.

Preliminary cover art

In order to weave a complex story such as this, it takes hours of sifting through threads of history; research on the causes of the Great Recession and the impact on the lives of ordinary people. In order to build the Arapaho shaman character who becomes the lightning rod at the center of the story, I read indigenous history books such as The Wisdom of the Native Americans and In the Hands of the Great Spirit.

But a book that truly resonated with me was an incredible work by Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, published initially in Hebrew (2011), then in English in 2014. This is a stunning book on the anthropology of homo sapiens, and various competitor humanoids, up to the present time. This is not a dry rendition, it is filled with Harari’s philosophical spin on the effects of capitalism, government, and religion.

I was particularly interested in researching the hunter/gatherer period before homo sapiens became trapped into the agricultural revolution, which begs the speculative question—how would society look if that leap hadn’t occurred? And as my novel will attempt to reveal—what if a new messiah led us back to the hunter/gatherer life—turning away from modern society?

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

SUBSCRIBE TO K.E. LANNING TO RECEIVE BLOG ARTICLES AND AUTHOR UPDATES

What if the ice caps melted . . . in one human lifespan?

The Ascent of Robots

In 1950, Isaac Asimov published the novel, I, Robot, and within that work, he outlined his “Three Laws of Robotics”:

1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Humanity is on the cusp of a true robot revolution—will we be so prescient?

The technology shift in labor started with the computer age in the late twentieth century, but intelligent robots will be the coup d’etat for the labor market. Others are writing about this coming phenomenon: science fiction writer Liu Cixin is a nine-time winner of the Galaxy Award in China for his work and recently penned an article for The New York Times, titled, “The Robot Revolution Will Be the Quietest One.” [https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/07/opinion/the-robot-revolution-will-be-the-quietest-one.html] He writes of a world run by robots more intelligent than we are…a world where humans become no more significant than pets.

Will society re-segregate not on lines of race, but divided between the rich upper class, the robots they control, and ‘the rest of us’? Or perhaps we’ll witness a societal backlash, with a new rise of Luddites rioting in the streets, destroying robots, while crowds chant as they upload the scene to social media?

But the Luddites didn’t prevail at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution and neither will the coming Rage Against Robots.

Is it all gloom and doom? We humans have survived the industrial and computer revolutions, shifting with an ever-changing labor market, though there have been winners and losers in the game. There will be a huge demand for the care and maintenance of robots—feeding those brains with code and repairing the intricate mechanisms—harking back to a time when our ancestors cared for the faithful plow horse.

But one major impediment stands in our way—we humans are populating ourselves out of a planet even without the competition of robots. On our current trajectory in propagating the Earth, we will overload the boat and sink into the sea from where we came, unless we stabilize our population growth and find sustainable methods of living. The world populations must embrace education and birth control—our survival depends on it.

Darwin said, “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.”

And change we must, because the Ascent of Robots is upon us.

K.E. Lanning, author of A Spider Sat Beside Her and The Sting of the Bee [2018 release]

First published on January 26, 2017, in OMNI https://omni.media/the-ascent-of-robots

Rest in Peace, Edward

The world knows Edward Albee as an incredible playwright—his wry and acerbic wit revealing those dark human characteristics that no one wants to be revealed. He was a teacher, a mentor, and a supporter of the arts. This last avenue, in the vibrant art scene of Houston, is where Edward and I crossed paths. It was the 1990s; he was teaching at the University of Houston and producing his plays in various venues. I had an art gallery in Houston, TX, and I came to know Edward as a discerning and well-respected art collector.

I saw a show of some of his collection at the Hiram Butler gallery in Houston; it was a lovely exhibit and I was intrigued by the scope and depth of the artwork. His eye was phenomenal and he focused on up and coming artists with a message to tell. About that same time, I had begun curating a series of shows based on books that interested me in the content and title: The Garden of Eden (Ernest Hemingway), Brave New World (Aldous Huxley), and Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (Mackay), as a few examples. I invited various artists from the unknown to the world famous to exhibit—they drew crowds—and Edward. After the opening of the Brave New World show, he wrote a letter to me asking a question on one of the pieces and we started a dialogue about the social implications of the show.

Edward began to frequent the gallery and I remember on several occasions, he would find some small sculpture in the back gallery (he loved three-dimensional work), cradling it in his arms as he toured around. He bought several pieces from the gallery and always stopped to chat when we ran into each other on the gallery circuit.

After I closed the gallery and began to find my voice in writing, he spoke with me about that, too. Our conversation wasn’t huge or life-changing, but sometimes having someone like Edward simply acknowledge your journey is enough.

Edward, you made a difference in my life. Thank you, and rest in peace, my friend.

K.E. Lanning