Animal Farm – 75th Anniversary and chillingly relevant

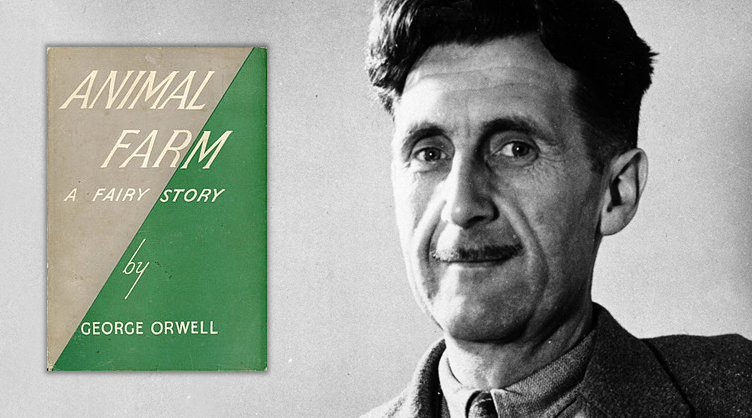

First edition cover (1945) for Animal Farm and author George Orwell

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others. Animal Farm, 1945

In the preface of the allegorical novella, Animal Farm, Orwell described the source of the idea of setting the book on a farm:

“...I saw a little boy, perhaps ten years old, driving a huge carthorse along a narrow path, whipping it whenever it tried to turn. It struck me that if only such animals became aware of their strength, we should have no power over them, and that men exploit animals in much the same way as the rich exploit the proletariat.”

Orwell began writing Animal Farm in March of 1943 and completed it in April 1944. Several publishers refused it, considering it an attack on the Soviet regime and, despite Stalin’s murderous purges, Russia was a crucial ally during WWII. Finally published on August 17th, 1945, Animal Farm resonated in the post-war era, achieving worldwide success, and Orwell became a celebrated figure.

Orwell described Animal Farm as a “fairy story” or fable reflecting the Russian Revolution and Stalinist era of the Soviet Union. The book weaves a story of farm animals who, led by two pigs, Snowball and Napoleon, rebel against their human farmer and attempt to create their own free and equal society. Power mad, Napoleon overthrows Snowball and the utopian society devolves into a dictatorship, with Napoleon now indistinguishable from the human owner the animals had ousted. Animal Farm was the first book in which Orwell tried, “to fuse political and artistic purpose into one whole.”

ORWELL’S EARLY LIFE

George Orwell was born Eric Arthur Blair on June 25th, 1903 in Motihari, India. He grudgingly attended Eton, and though not a stellar student, he was known as a practical joker and a young man who argued for argument sake. In 1922, he sailed to Burma and worked as a police officer until he contracted dengue fever in 1927, after which he returned to England. At this point, among a variety of occupations, he began his writing career, but Orwell’s tenuous health would continue to plague him for the rest of his life. Inspired by the River Orwell in Suffolk, England, he took on the pen name George Orwell in 1933 for the publication of his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London.

In 1936, Orwell went to fight against Fascism in the Spanish Civil War, but over time, he became disillusioned with the Communists, and after he and his wife escaped from Spain, he considered himself forced into the role of pamphleteer. “The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.”

ORWELL THE WRITER

Contemporaries of Orwell paint the picture of a man who struggled to become a writer through long periods of poverty, failure, and humiliation, but he turned the sweat and agony into literature [paraphrased from Fyvel]. Ben Wattenberg stated: "Orwell's writing pierced intellectual hypocrisy wherever he found it." According to historian Piers Brendon, “‘Orwell was the saint of common decency who would in earlier days,’ said his BBC boss Rushbrook Williams, 'have been either canonised—or burnt at the stake'"

In 1940, Orwell wrote: "The writers I care about most and never grow tired of are: Shakespeare, Swift, Fielding, Dickens, Charles Reade, Flaubert and, among modern writers, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot and D. H. Lawrence. But I believe the modern writer who has influenced me most is W. Somerset Maugham, whom I admire immensely for his power of telling a story straightforwardly and without frills." Elsewhere, Orwell strongly praised the works of Jack London, especially his book, The Road.

He wrote an essay in 1946, “Why I Write,” in which he details his journey to writing. He professes four motives for writing:

1. Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful business men – in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they abandon individual ambition – in many cases, indeed, they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all – and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.

2. Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.

3. Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.

4. Political purpose. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people’s idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

And yet Orwell famously said, “Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness.”

First Edition cover (1949)

In 1949, George Orwell went on to publish his best-known work, Nineteen Eighty-Four, a dystopian novel of government repression and overreach. He created a terrifying world in which the citizenry is trapped in a constant state of fear of unending wars versus “others” and controlled by surveillance and propaganda. The unnerving echo of political manipulation of the truth tolls like a bell across our world.

Orwell died from tuberculosis in 1950 at the age of forty-six, but his profound tales of totalitarianism are still relevant in their searing exposure of today’s societal ills.

IN THE YEAR 2020

On the seventy-fifth anniversary of Animal Farm, we’ve made progress on civil rights, women’s rights, and LGBTQ rights—and yet the rich and powerful are still “more equal” than others. How can this be? Where is the line between political satire and reality in our new millennium?

Inequality suits the powerbrokers, and so the deep-seated irrational fears of race, misogyny, sexual orientation and xenophobia are exploited by clever puppet masters in order to maintain control. And why Margaret Atwood’s chilling novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, has struck a deep chord within our not-so-perfect union in America and the world.

The sad truth of human nature is that bigotry is a cudgel of dominance—Orwell’s Animal Farm endlessly played out in real life, enabling a machine of intolerance—an institutional hierarchy. For those who doubt this system of privilege and power exists, just look into the eyes of Derek Chauvin as he coldly executes George Floyd—he knew was protected by this supremacy. Orwell’s words haunt us to this day: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

August 17th, 2020

K.E. Lanning, author of The Melt Trilogy

My in-depth interview with Margaret Atwood (audio version at top).

Many thanks to Wikipedia and The Orwell Foundation for background on George Orwell.

This article was also published on FUTURISM.